Long, long ago…

When Michael Eisner and Frank Wells took the reins of The Walt Disney Company, their agenda was clear: Movies. Both executives came from the film business, and they were brought into the studio on that basis. The problems that had faced the previous management team were firmly in the theatrical realm; theme parks were flourishing and a constant, dependable source of income, and the company was branching out into new realms of cable television and consumer products. But the film business was languishing, and the studio had a number of high-profile flops that eventually forced the issue and hastened the behind-the-scenes greenmail and wrangling that eventually led to the executive shift.

And so Mr. Eisner set himself to making movies, churning out a stream of inexpensive comedies featuring somewhat faded stars – and it worked. The concept of trying not for home runs, but shooting for singles, doubles, and triples paid off, and the studio’s fortunes slowly began to turn. But that wasn’t the only reflection of Eisner’s Hollywood-centric mindset.

MCA Inc., then owners of Universal Studios, had long planned to bring one of their trademark studio tour theme parks to Orlando – a vacation market that Disney had dominated since 1971. Yet only four months after Eisner arrived at Disney – at his first meeting with the company’s shareholders in February 1985 – the new CEO announced that Disney would be building their own studio tour in Florida. This came as a surprise to MCA; its veteran Chairman, Lew Wasserman, accused Disney of copying plans for a Universal park in Orlando which, they claimed, Eisner had seen years earlier. In 1981 Universal had approached Paramount as a potential financial partner in the venture and, as Eisner had been president of Paramount at the time, MCA insisted that he had been privy to Universal’s ideas for a Florida studio tour. Before Disney’s own studio project was announced, Wasserman and MCA president Sid Sheinberg had even approached Eisner and Wells to propose that Universal and Disney embark on a studio attraction together on Disney’s Florida property.

Needless to say, the heated accusations that accompanied the announcement of what would become the Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park kicked off the “studio wars” in an atmosphere of open hostility. The situation did not improve in early 1987 when Disney and the city of Burbank announced plans for a new attraction in the heart of the city itself – the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot.

In an attempt to revitalize its city center, Burbank had been working with developers on the $158 million Towncenter mall but, when a fourth anchor tenant failed to emerge, the project fell apart. Brainstorming a way to save the project, Councilman Robert Bowne was said to have asked, “Why don’t we let Disney dream a dream for Burbank?” Councilwoman and former mayor Mary Lou Howard ran with the idea and, behind the back of the City Council, approached Eisner with the idea.

Howard and Burbank City Manager Bud Ovrom lunched with Eisner at Disney’s executive dining room on January 22nd, 1987, and found the executive to be very enthusiastic about the idea. During a two-hour lunch, Eisner described ideas for the project while sketching on napkins and the tablecloth. As he later recalled, “I was having a fabulous time. That’s what the creative process is all about.”

On April 24th, Burbank Mayor Michael Hastings traveled to Walt Disney Imagineering for a presentation on the potential project. After the 2-hour pitch, Hastings stormed out of the room; “I went out of there like a bull in a china shop,” he later said. “I was imagineered into a world none of us had been exposed to. I felt like our staff was being waylaid by Mickey Mouse. I went away thinking, ‘Never in my city.'”

Unsurprisingly, Hastings found that few other Burbank residents shared his qualms. After days of discussion with his wife, friends, and city residents, he changed his tune. As he later put it, “The majority of the feedback I got was, ‘Tread lightly on it, let’s see what it’s going to be.’ I also started weighing the alternatives, and sorted things out. Then I was slam-dunk in favor of it.” He seemed to finally comprehend what a boon a Disney project could be for the city, saying, “Anything else we would put there would be ordinary. It’s time that something unusual and unique happens here. We’re all used to Burbank being one way. We do a real good job of serving our senior citizens. But, unless we want to expand the Joslyn Senior Citizen Center to cover two-thirds of Burbank, we’ll have to do something else for the rest of our demographics.” “Something like this,” he realized, “would give the whole city a shot in the arm.”

To illustrate how “lucky” Burbank was to have such an opportunity, Eisner showed Ovrom and other officials a videotape the company had received from the city of Dallas featuring local businessmen, developers, restaurateurs and “children in tuxedos” begging Disney to come to their town.

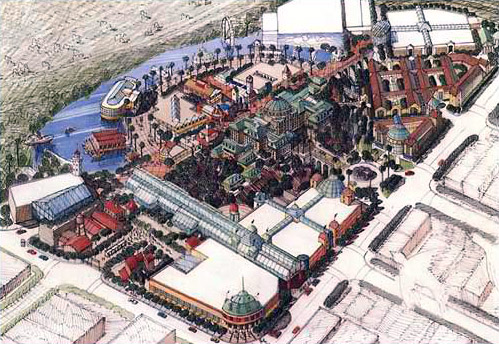

On May 5th, 1987, the Burbank City Council voted unanimously to grant Disney an option to buy 40 acres of prime real estate at the corner of 3rd and Magnolia for the bargain-basement price of $1 million. The Council had been wowed by Disney’s pitch for “The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot,” a new concept for a retail and entertainment district that shared a great deal of DNA with the Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park, then under construction in Florida, as well as other in-development Eisner era projects such as Typhoon Lagoon and Pleasure Island. The Backlot would showcase “behind-the-scenes Hollywood themes, street performers, live theater, Disney animation tours and operating radio and TV media centers,” at a cost of $150-$300 million.

The deal guaranteed that Burbank would not negotiate with other developers, and that Disney had six months to develop detailed plans, a parking layout, and a proposed construction schedule. After further approval by the City Council, Disney would have six more months to further develop and revise their plans. At the end of twelve months, either side could pull out of the deal if they were dissatisfied with its progress.

Nine drafts of the agreement had been written before the deal was struck; upon signing, Eisner told Councilwoman Howard, “This is your project.” Howard herself was pleased, telling the press, “It’s time the city had something that Johnny Carson wouldn’t make fun of.” City Manager Ovrom sounded optimistic, announcing, “I am convinced the Disney development has greater potential to generate more revenue and economic spinoff for the city over the long haul than any traditional center.” Yet Eisner himself sounded a word of caution; speaking to the media, he warned, “We’re still hoping that this project that we have described is economically feasible. The issue is not what the land cost. It’s whether we can deliver the dream, financially.”

But what was this dream? For starters, a third of the acreage would be devoted to retail, with hopes for two major international retailers. Disney’s existing studio lot, crammed to the gills with all the new film and television production, needed satellite office space and expanded backlot facilities; the Burbank project would feature a relocated Feature Animation department and Disney Channel offices. Much like the new Florida park, it would feature the MGM film properties licensed by Disney in 1985. A six-story parking deck would be topped by a “Burbank Ocean”, and a massive waterfall would conceal the structure from the neighboring I-5 freeway.

But for a more detailed look at the concept, let’s travel back to that day in 1987 when Disney made their pitch to the Burbank City Council. Thanks to local public access television, the proceedings were broadcast and captured for us to see. Here is a blow-by-blow look at the new project featuring an unnamed individual (let me know if you can recognize the voice) and a fresh faced, 32-years-young Imagineer Joe Rhode. This is actually a rare chance to get a look at something approximating a WDI pitch session and, seeing Rhode go, you can imagine why he’s been successful in getting some pretty wacky projects approved. He’s… enthusiastic. Overwhelmingly so. I can imagine all these stodgy Councilpersons voting for the project out of desperation as to not get swept away in his tsunami of rhetoric. It’s pretty impressive to see, even if Eisner is inexplicably being a grumpus throughout. Let’s take a tour, and see what could have been…

Did you survive?

What’s hilarious about this concept is just how many Eisner-era fetishes and tropes it features: A stranded ship, much like Typhoon Lagoon. Nightclubs much like the plans for Pleasure Island. Wild visions of backlots and studio tours and buildings with false fronts that you can walk behind and see that they’re fake. Something based on Splash. And, most importantly, a Ferris wheel. Always a Ferris wheel.

But whether it’s just Mr. Rhode casting his spell on me or not, a lot of these ideas are very, very cool and deserve a second look today. Let’s review, using this handy guide:

It was very important to the project’s success that it serve, primarily, the people of Burbank and match its environment smoothly. To face the low-lying residential zoning along 3rd Street, the Backlot would present a smaller urban scale before rising up to 3 or 4 stories on the side facing the local high school. At the corner of 3rd Street and Magnolia Boulevard would be a 2-3 story anchor department store from a major national or international chain. The notion was that the Backlot would present a welcoming and “normal” face to the outside world, melding seamlessly with its environment. But as guests proceeded further and further into its interior, things would get increasingly themed and zany. A regular Burbank shopper would be able to pop in and buy some socks without having to enter the tourist areas, as all the entertainment would be contained at the far end of the complex.

The created mythology of the space is hilariously stereotypical Eisner-era mystique of the Meriwether Pleasure variety. Long ago, you see, in days of yore, studios had big backlots where they shot their films. As production techniques improved, though, location shooting became more common and the old studio backlots died off. But at the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot, according to the story, Disney had reclaimed its old, abandoned backlot as a shooting location and it’s back in use today! Sure there are shops and restaurants in the old-timey movie sets, but they’re still used for shooting! Look! There’s Bette Midler shooting her saucy new Touchstone Pictures comedy! Take some pictures, folks – who knows? Tomorrow this set could be a whole other city or Ancient Greece or outer space! Anything can happen in the movies!

These “original” backlot areas would be contained in the Golden State Mall, a shopping district featuring Old West movie sets depicting a Gold Rush era town. These sets would be visibly “fake” with half-finished walls and facades separated from interior spaces. One of the first shopping areas guests would encounter, it would become a performance space at night. One venue in particular, the old train roundhouse containing a country & western and comedy club, still sounds like it would work today. Especially interesting would be the old locomotive converted to use as a cappuccino machine, peanut cooker, and “potato roaster” which would also illuminate the stage with its front light. Leftover explosives from mining would be used to construct the bar. The idea of having different characters in each area – related, no doubt, to the Disney-MGM Studio Theme Park concept of “streetmosphere” – would result in these different clubs and areas having wacky denizens and proprietors (and also “girls with long legs doing kicksteps”).

Other streets within the Backlot would be themed to New York, European cities, and Tokyo’s Ginza district. Ginza was another long-time Imagineering target; it was proposed for the very first version of World Showcase in the 1970s, and was announced as an expansion for Epcot’s Japan Pavilion in the 1990s. Much like the original studio lots, the Backlot would feature streets based on ancient or mythical places, from Pompeii to Angkor Wat to Ancient Egypt. As Rhode promises, we can meet for lunch “under the statue of Ptolemy.”

On the upper levels of the Backlot, separated from the shoppers and strollers, would be the nightclubs. Disney envisioned a number of venues from “Club Heaven”, located in the Ginza area, to a Caribbean-themed Calypso club. Another proposal was for an odd-sounding club where, for entertainment, guests would sit in a chair and operate Audio-Animatronic figures. In the area themed to lost cities – don’t worry, “you don’t need to confront the Sphinx” – a club full of mystical artifacts would pull historic figures through time as part of a “cinematic event.” In this storage warehouse, guests would be surrounded by props used in great movies which, imbued with magnetic powers, would revive the personalities of the actors who once used them. As guests dined, characters such as Cleopatra, Marc Anthony and Ben Franklin would play out a story around them.

Providing a respite from this madness would be the California Canyon, a quiet and relaxing space where waterfalls and a trout stream would flow in the shadow of two towering structures. Looking down from offices, balconies, or restaurants, all designed in a California bungalow style, people could enter the canyon for an evening stroll among the sycamore groves.

Rising from the canyon, and the “crown of the entire project”, was to be the Hollywood Fantasy Hotel. Surrounded by Rhode’s trout and squirrels, each floor of this remarkable hotel would be themed to a different film genre. Imagine staying in a room straight out of film noir! At the top, Imagineers planned the Celestial Diner, billed by Rhode as “the most romantic place to have a meal in the entire west.” The restaurant does indeed sound spectacular, featuring a chamber orchestra and planetarium ceiling.

From these areas, guests could enter the more traditional entertainment areas of the Backlot. Straight from plans for the new Florida studio park, the Disney animation department would move to a new campus incorporated into the Backlot complex. Open to tours, and featuring a public museum for the Disney Archives, the campus would also feature a multiplex theater that could house annual animation festivals. In the Star Quality Diner, people could dine surrounded by movie memorabilia while their kids played on catwalks above. The Soundstage Restaurant would cater to family audiences, drawing from the “mythology” of Disney and MGM. This is where the Disney characters could be found, and where character meals would take place.

Also in this area would be a duplicate of Florida’s planned “Great Moments at the Movies” ride (soon to become just the “Great Movie Ride”), and an attraction teaching about special effects using Star Tours simulator technology. A three-camera video production studio would feature an attraction similar to Florida’s Superstar Television show, and the ubiquitous Videopolis Dance Club (soon to be found at both Disneyland and Florida’s Pleasure Island) was there to provide TEENZ with food and dancing with a sci-fi spin.

At the farthest extent of the Backlot was to be a waterfront entertainment district surrounding the 18-inch deep “Burbank Ocean”. Featuring a number of typical pleasure pier attractions, the area was meant to represent the Backlot’s old movie studio special effects tank which had been converted for use by guests. The Ocean would stretch to the horizon, blocking out the freeway, and cascading out of sign past the parking garage below. To a guest on the boardwalk, they would merely see the sun setting into the “ocean”.

Along the pier could be found a traditional funhouse and bumper cars “with a difference”; the Rockin’ Rollerdrome – later to appear at Pleasure Island – was also planned here, offering rollerskating, dancing, and dining while a DJ flew around overhead in a ’57 Chevy. Particularly clever was The Deep End, a restaurant with a 1950s beach theme that appeared to be housed at the bottom of a swimming pool. A faux water surface far above would create the illusion, combined with lighting effects and Audio-Animatronic “swimmers”.

Yet another vintage Eisner classic was Madison’s Dive, a bar once intended for Pleasure Island and themed to the 1984 hit film Splash. This crabhouse’s windows would look out into aquariums, giving a sense that diners were deep underwater looking out at passing sea life.

Emerging from the Burbank Ocean was to be an enormous Ferris wheel, which, lodged halfway into the building like a stuck quarter, would bring guests out of the Ocean six stories off the ground. But this didn’t hold a candle to the other attraction sitting on the precipice of the waterfall – the Fish Out of Water Restaurant.

Housed in a ship stranded on the edge of the Burbank Ocean, with six stories of waterfall cascading below, this restaurant would be based on the simple premise that – in perhaps the most immortal pitch ever presented by an Imagineer – “Something’s wrong, and beef lives in the sea.”

Something is wrong. And beef… lives in the sea.

Guests seeking to dine would have to board a rowboat from the pier and make their way out to the stranded ship; inside would be traditional seafood restaurant decor but, instead of fish, diners would find the best steakhouse in L.A. Instead of mounted swordfish, the walls would be lined with stuffed steer. Lobster traps twelve feet long would hang from the ceiling. Paintings and pictures would show massive trawlers fishing for cow, schools of cow leaping from the water, Cousteau swimming with the cows, Hemingway showing off a bison he had reeled in…

Tell me that wouldn’t be spectacular.

On the deck of the ship, a balcony and bar would provide guests with a tasty beverage and spectacular view of the Valley. And if that isn’t reason enough to mourn the loss of this project, nothing is.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, and immediately upon announcement of the project, MCA Inc. responded to Disney’s plans with outrage. The “studio wars” were already two years old at this point, and not only had Universal decided to proceed with a studio facility in Orlando, but had also determined to expand their entertainment offerings in the hills north of Hollywood. Universal saw Disney’s entertainment complex as a direct threat to their plans for a similar district in Universal City, and lodged a complaint with the Burbank City Council.

Disney, MCA believed, had gotten a sweetheart deal, and other companies should have had a chance to bid on a project for the Burbank land. Burbank admitted that Disney got a good deal, paying $1 million – 57 cents a square foot – for land that other developers might have paid $50 million for. The city had pushed for more money, but Disney stuck to their initial offer. “The break we got in the cost of the land,” Eisner insisted, “will be so compensated by what we spend on just bricks and mortar on this property that Burbank will get back its fair amount of investment.”

Also contentious was the issue of parking; Disney felt the city should provide municipal funds for the structure, which could have cost as much as $35 million, while the city thought that Disney should pay. Eventually the city agreed to give Disney $1-$3 million in property tax breaks to go towards the construction of parking facilities.

In June 1987, MCA filed suit to overturn the deal and force public negotiations with other companies. MCA accused Disney executives of blackmail, and claimed that they had offered to pull out of Burbank if Universal would abandon their plans for an Orlando park. Disney denied the accusation.

But MCA wasn’t Disney’s only legal issue. The chairman of MGM-UA, Lee Rich, claimed that Disney had no rights to use licensed MGM properties or names outside of Orlando. “We were very upset about it,” Rich said of the Burbank deal. “We’re going to do anything we can to get them not to use it.” For his part, Eisner felt that it was “crystal clear” that Disney was perfectly within its rights, and pointed out that they already planned to use the MGM name in multiple overseas projects.

As the year passed, more problems emerged. In October 1987 Disney claimed that they’d had problems attracting major retailers to the project and that the Backlot may have to be “scaled back” to become sufficiently profitable. By February 1988, the estimated cost of the complex had risen to $618 million, although Disney had entered talks with British retailer Harrods. Mitsukoshi of Japan, although not yet contacted by Disney, openly expressed interest in the project as well.

But it was not to be. On April 8th, 1988, Disney sent a letter to Burbank officials withdrawing from its agreement to buy the land. Alan Epstein, Vice President of the Disney Design Company, called the decision “extremely difficult” and claimed that Disney had already spent $2.5 million and 22,000 working hours developing the concept.

In the end, the death knell for Burbank’s Backlot was a familiar and unwelcome line; in the words of Disney spokesman Tom Deegan, “We gave it the pencil test, and it didn’t pass.”

Apparently no one told him about BEEF LIVING IN THE SEA.

I’m with you on this one, Joe. I’ll go to Lowe’s and pick up some lumber and meet up at your house. Time to start building.

Wow. I had never heard of this project until today. It is a shame they never got it off the ground, because it would have been built at a time when Disney was still doing things right (somewhat).

Also, good to see you posting new things again…I was begining to think you had abandoned the site.

HPX

Thanks! Yeah I didn’t mean to take such a long “vacation”… things got away from me. There’s tons of stuff I want to do on here, though.

This was a cool project that not many people know about or remember. I’d heard about it, but had never ever seen this much detail about it before I saw this video. I think it would have been pretty cool.

Great read, thanks for sharing this all! Interesting to think that we could have had such a fragmented Disney experience in SoCal if some of these plans ever became a reality, between this and the DisneySea concept for Long Beach. That said, it would have been pretty nice to have something like this over in Burbank, especially those kooky restaurants!

If this actually happened, I wonder if it would have been able to compete with CityWalk which opened just 5 years after the plug got pulled on these plans. Do you think CW was Univeral’s response to this?

I think at the time Universal was working on what would become CW. Part of their objection to this Disney project was that they didn’t want the competition!

[…] Michael Crawford shares information regarding The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot, an interesting retail concept that never came to […]

To people who have tried to comment lately and have not been able – sorry, but apparently the last time I updated the software there was some conflict that screwed up commenting. Fixed now, though!