In a speech during the 1970s, author Ray Bradbury famously referred to Imagineering as a “Renaissance organization.” That was an apt metaphor; that first generation of Imagineers contained a remarkable collection of what could legitimately be called Renaissance men (and a handful of Renaissance women as well). These artists, many of whom had been culled from the realm of live-action motion picture art direction as well as Disney’s own animation studio, had not grown up going to Disneyland and dreaming of theme parks; they had seen the world and, like Walt himself, were fascinated with a slew of seemingly unrelated and esoteric subjects.

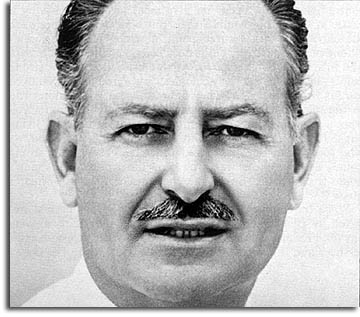

Over the years, though, the mantle of Imagineering’s resident “intellectual” seems to have settled on John Hench. Another long-time Disney staffer and former artist at the animation studio, Hench was the reserved, studious sort. After Walt’s death, when individual Imagineers started to come to the fore in the media, Hench’s position at the top of the WED pile ensured that he received lots of print coverage as Disney tried to figure out what they were going to do about EPCOT. During this time, he publicly began to discuss his philosophies about “the architecture of reassurance” and what, exactly, made Disney Disney.

It’s hard to tell how much of this Henchian analysis went into the original design of Disneyland. Although I hope it’s obvious that I adhere to the viewpoint that theme parks are art, Hench’s musings have always struck me as ex post facto philosophizing; they seem better suited to figuring out why Disneyland worked as well as it did than as a predictive method of effective design. A problem I often have with deep-text analyses of themed design is that it assumes intent that I don’t always believe was there. It strikes me that most of the original Imagineers – including Walt himself – were deeply intuitive artists who judged things solely by whether they liked them or not. Not for nothing was Walt’s famous sign-off “That’ll work.” I’ve always interpreted that as a literal statement of fact, not as a prelude to “That’ll work to help subliminally evoke race-memories and instinctual reactions in the hippocampus to evoke the proper reaction.” That might be what’s actually happening, but I can’t believe that the designers thought it out to that point. You don’t crank out artwork at the rate Marc Davis did by stopping to plan and analyze the semiotics of the piece; surely he was simply drawing things that he liked, or thought entertaining?

Walt’s artists were indeed brilliant, but I think of them more as intuitively so rather than intellectually so. They were well-read and well-traveled, and those experiences and knowledge informed their design, but I don’t feel like they set out to rationalize everything beforehand. For one thing, there was little time to do so. For another, Disney attractions typically included several “authors” and eventually the ultimate editor, Walt himself. I can’t imagine Hench going on like this back in a design meeting with Walt; it’s mere speculation on my part, but I can’t imagine Walt having patience for such things. I very much doubt that Walt cared why things worked, since he could so quickly and intuitively tell that they would work. Why stop and think about it if it’s instinctive?

Nevertheless, for those of us who aren’t geniuses (and for some of you that are), such analysis can be fascinating. There is a reason why Disneyland works. There is a reason why Disney was successful in the first place, and it wasn’t good marketing or good advertising (although that never hurts). It was because of a qualitative difference in the world Disney created as opposed to what could be found elsewhere. And the reason that many of us get upset with the wayward drift of Disney parks over the last 15-20 years or so is because too many decisions are not being made on the instinctive or intellectual basis that made Disney famous in the first place.

But that’s a rant for another day. What follows is an article from New West magazine in December of 1978, with Hench’s thoughts on what makes Disneyland work. There’s a touch to the hagiographic about the article, but it’s an interesting piece and a nice look at Hench’s mindset at a critical time for Imagineering. Just a few months prior, Walt Disney Productions had announced that it would, in fact, proceed with development on EPCOT Center, and between that project and Tokyo Disneyland, WED was entering the busiest period of its history.

CHARLIE HASS on the Magic Kingdom’s master manipulator

DISNEYLAND IS GOOD FOR YOU

You’re waiting in line for Pirates of the Caribbean, inching along and feeling not too great – a result of injudiciously going to find out what had gotten into the Matterhorn so soon after the Casa de Fritos – and you are fingering the “E” ticket in your breast pocket every thirty seconds or so even though it’s going to be fifteen minutes easy before you reach the turnstile, and in those fifteen minutes you think about, oh, all kinds of things: sex, the Sox, the drive here, the drive home. Your thoughts are your own business, even at Disneyland.

But it may be instructive to consider a few things you are probably not thinking about as the line moves slowly and surely forward. The real good likelihood is that you are not dwelling on the confidence engendered in America by industrial progress and national expansion in the late nineteenth century, nor on the importance of central fortresses to the earliest cities, nor on the pleasure of prehistoric tribes at sharing fresh-killed game. You might happen to hit one of these if you majored in anthropology, maybe two if you’ve been reading yourself to sleep with Man and His Symbols. But three?

Just the same: Out of mind, at the Magic Kingdom, is not necessarily out of sight. In your least adventuresome moments – window-shopping Main Street, shaking hands with Mickey – you are firmly encircled by subtle but deliberate visual signatures of those remote notions you’re not thinking about as you languish in line, and of several more of human history’s greatest hits. Disneyland, as one of its key creators explains, draws much of its legendary power to entertain an international audience of all ages from its skillful incorporation of aesthetic effects that find their resonance in the visitor’s genetically inherited ancestral memories – a nostalgia of considerably longer standing and more compelling power than a childhood devotion to Dumbo.

A portentous claim for an amusement park, but then it is a major article of Disneyfaith that Disneyland is not an amusement park but a themed entertainment experience. Disneyland is to an amusement park what a well-designed shopping mall is to a rundown city block of randomly arrived storefront businesses – an equation to conjure with, because it is necessary to know why simply being on a city street is so bad for your evolutionary capabilities in order to know why being at Disneyland is so good for them. To understand that, and the whole process that brought atavism to Anaheim, you have to talk to John Hench.

"The Inner Disneyland - Walt's original theme park runs on elaborate psychological clockwork, revealed for the first time in the words of John Hench, executive vice-president and chief operating officer of WED Productions."

John Hench, who is 70, is executive vice-president and chief operating officer of WED (Walter Elias Disney) Enterprises, the division of Walt Disney Productions responsible for the design and execution of attractions, including all the rides and shows at Disneyland and Walt Disney World. Trained as a painter before joining Disney almost 40 years ago, Hench worked on live-action and animated features – as an artist, set designer, and special-effects technician – before Walt Disney put him to work on the planning of Disneyland in the early fifties. Combining his practical experience with a wide range of research, Hench has become the Disney organization’s ranking theoretician on how movies and theme parks can be programmed to produce effects on the unconscious as well as the conscious mind – the rightful resources of the informed entertainer, or the tactics of manipulations, depending on your point of view.

Hench is an intellectual out of Disney casting: He is genuinely brilliant and articulate, and his theories ofter get to complex and exotic places. But he employs a softening measure of colloquial offhandedness that makes him seem an unthreatening regular guy. And a company man: His deferrals of credit to Walt Disney are frequent and fond. Though he is balding and his face is well lined, he undercuts the appearance of age with vigorous speech and movement and a casual look. During a recent conversation, he wore a bright ascot under a shirt on which several Mickey Mouse heads – the same color as the rest of the shirt, but woven in a different density – were visible in certain lights. His mustache, silver and neatly trimmed, is reminiscent of the late Disney’s. Sitting in a borrowed office at the Disneyland Visitors’ Center, Hench describes Disneyland as a “storyboarded” environment, one in which the sequence of impressions and experiences is carefully regulated by a supervising intelligence.

“It is easily understandable when you think of it like a film and how identity is controlled in a film. Identity is a figure-ground relationship: Scene five takes its identity from scenes one, two, three and four. If you put scene five against that background, you understand it, but if you just dropped it in the audience’s laps they wouldn’t know what was going on. There’s a flow of relations that you must have so that their attention doesn’t wander. We did a slide show once, called Good Show – Bad Show, to demonstrate why Disneyland is different from someplace else, why there’s a sense of order here and what order is supposed to do to you. And the photographer who put it together came up with a wonderful example of a bad show. He took a picture of that Gothic tower at Franklin and Highland, where is a pure piece of Gothic – it speaks to us even yet, after all these years. That Gothic message didn’t come out of one man’s head, but out of a group movement, like a folk song. And right in front of it is a big gasoline sign.

“Well, one contradicts the other. They juxtapose. And the Gothic tower doesn’t do the gasoline any good either, you know. A city is made up of all kinds of things that way, unrelated things, and it doesn’t add up to anything except chaos. We have a couple of million years’ experience with chaos, and we know that it’s the next step before conflict, and we have experience with conflict also, and it’s something that doesn’t endorse our survival potential. So cities are threatening.

“But the order here at Disneyland works on people, the sense of harmony. They feel more content here, in a way that they can’t explain. You find strangers talking to each other without any fear. You actually find people patting strange kids on the head, which of course they wouldn’t do anywhere else. If you walk down a city street – just any modern city, Chicago, Tokyo – you don’t look people in the eye. God, you’d be in trouble if you did that! You don’t smile at a stranger. They’d only think you were making an ass out of yourself. And so you lose some of the faculties that you need in order to evolve successfully.

“So people come to Disneyland, and they’re aware – through this extraordinary mechanism that they inherit from their ancestors – of the kind of harmony here. Things seem to know each other. One side of Main Street is aware of the other side. It was planned for this very effect, and who else but motion-picture people, who design sets, could do it? Walt understood the relation between scene one and scene two, he knew how to identify something and how to hold the identity due to something the Germans call gestalt. Nothing has an identity of its own until it’s related to something else. If you can control that relation, you can control identity. You can use images in a literate way. And Walt sensed what you could do with entertainment. Entertainment is usually thought of as an escape from problems, an escape from responsibility, but as far as I know he had an original idea – and there are some practicing psychiatrists that happen to agree with us, that what we are selling is not escapism but reassurance.”

That reassurance, Hench says, comes not only from the harmoniously designed environment but from thrill rides such as Space Mountain and the Matterhorn, which expose the rider to a threat and then take the threat away as the ride ends. “It goes back to the one universal human dynamic – survival,” Hench says. “We’re here today because our ancestors were good. They knew the patterns of survival, they knew how to do it. The others, who were foolish or didn’t pay attention to it, are not here at all.

All social groups train for the coming challenges of survival. Even puppies play at battle. What we do here is to throw a challenge at you – not a real menace, but a pseudo-menace, a theatricalized menace – and we allow you to win. Like Space Mountain. You might feel threatened on that. You feel that you’re going way to fast for safety. Some people come off there with a dose of adrenalin like they haven’t felt for a long time. They might be kind of hyperventilated – but they win, and they feel good about it.

“The psychiatrists are beginning to agree that survival is our single dynamic. We tend to think of our aesthetic sense, for example, or our sense of ethics, as something separate from this, but if you really look at it, ethics are quite obviously associated with survival – you know, you belong to the tribe,” Hench continues, “you don’t lie to the leader, and so forth.

“Most people don’t really understand how vision can be part of this dynamic, but obviously, the better you use your eyes, the further away you can size up a situation and relate it to survival or its opposite, the better off you are. So those of us who are here today, whose ancestors survived, are very good at relating images together. Those people in primitive times who waited until they put their hand on it and felt it and said, ‘It must be a saber-tooth tiger’ – those people have no representation at all here today. So for us, the eye is overpowering, and for that reason Walt particularly used and exploited visual images. He knew they would get through in front of sound every time – in fact, we did some experiments, taping dialogue over a film situation, and distorting or contradicting the visual just to see how much attention would be paid to the narration. Well, people weren’t even aware that there was a contradiction because they never heard it. The eye dominated.”

It is Hench’s reading and thinking – along with the attentions of sympathetic psychologists, architects and urban planners – that has brought these ideas into currency in the Disney organization. “I suppose I’ve been the one to talk about it the most. But it was always here – Walt said it in various ways. You have to understand that Walt was a highly intuitive man. When we were building the little stagecoaches, I said, ‘Walt, God, look at this thing, we’re putting leather straps on it and everything else – it’s perfect. I don’t think they’re going to appreciate it.’ And he said, ‘Yes they will,’ and he gave me a lecture on understanding people. He said, ‘If they don’t appreciate it, if you do something and people don’t respond to it, it’s because you are a poor communicator. But if you really reach them and touch them, they will respond,’ he said, ‘because people are okay.’ How about that? He really believed that people are decent. It’s a matter of bringing that out, letting them know who they really are.

“I suppose some of our thinking stems from Jung, and from Freud, too; Freud came around the edges of it, but he didn’t really get into the basis of the threat. He understood that sexuality is naturally a very strong point of the survival mechanics, but – well, people have a problem because they were threatened so severely when they were young. They were left alone, or their mother didn’t love them, or some damn thing, and so they build up a defense, and that’s the source of all their trouble. And both Freud and Jung felt that you shouldn’t touch that defense because the threat is so overpowering that you need the shielding, that the defense is the only thing that keeps the guy alive and working. But there are a few people practicing now that don’t mind walking right in there and spreading that thing out – and again, it’s always a threat. And we have a number of psychiatrists who support our work, who’ve discovered that there’s something beyond an amusement park here. Because it works on people. It obviously works on people.

“If you’re at a state fair or something, everything clamors for you, so you look and you look and you try to make sense out of things, you try to decide and you constantly make a lot of judgements. But here, when we come to a point in the park that we know is a decision point, we put two choices. We try not to give them seven or eight so that they have to decide in a qualitative way which is the best of those. You just give them two. Then we get the guy farther along and he has another choice, but we’re not giving him four to being with. We unfold these things, so that they’re normal.

“It’s admitted that the shopping malls – the whole ‘malling of America,’ I think is the expression – comes from Main Street here in Disneyland. They suddenly discovered that they could build a shopping mall and make it work a lot better by just observing what happened here. Their observation is only partial, it didn’t penetrate too deeply, but they knew they wanted to make a sense of place. And how is a sense of place achieved? Simply because every member of the thing, every facility, agrees on what the place is. One building recognizes the existence of the other. There’s plenty of diversity, but there isn’t contradiction.”

Whatever the proportion of intuition to intention, the Disney studio at its best – in animated features such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Dumbo, Fantasia and Peter Pan – has taken frequent advantage of the powers of myth and symbol, and the psychology of color and form. Animation, with its almost unlimited vocabulary of colors and motions, is in some ways an ideal laboratory for testing the effects of moving shapes on the viewer’s emotions. The Disney features are lessons in the use of those effects: objects whirling in circular symmetry, friendly roundnesses played off against threatening angularities, shapes dissolving into other shapes with a revelatory facility that recalls dreams. In Fantasia especially, but in the others as well, mythic themes of fear and reassurance are played out in various costumings, with light quite literally triumphing over dark again and again.

One of the most popular criticisms of Disney, in fact, is that the studio’s films have neutered myth material, replacing instructive complexity and ambivalence with a placating singlemindedness. A similar complaint is that Disney’s live-action films and outdoor attractions depicting historical periods or foreign locales are prone to simplifying and sanitizing their subject matter to a misleading degree.

As Hench explains the Disney organization’s interest in psychology, subliminal impressions and the evolutionary value of harmonious surroundings, a more disturbing series of apprehensions comes to mind: One imagines a Disneyesque sorcerer playing one’s unconscious like a pocket calculator, punching in childhood triumphs and tribal anxieties so that some new thrill ride will come off like gangbusters. The themed entertainment experience begins to sound less like pricey fun and more like inexpensive therapy. But at what point does skillful entertainment turn to dangerous abuse?

“How do you abuse harmony?” Hench replies. “How do you give people too much of a sense of well-being? I don’t understand that, it’s hard to imagine. What is it? Euphoria? There has been research done by stimulating a part of the brain, using a very light electrical current and producing what seems to be pure pleasure. People think that satisfies every instinct – success, beautiful girls, the whole business all wrapped up in one. I suppose that would be an abuse. But there’s nothing like that in what we have in mind.”

But how about those – myself, say – who prefer the inchoate poetry of a city street to the more sterile harmony of Disneyland? Don’t some people thrive on randomness, surprise, disorder?

“They think they do,” Hench says. “And it’s true, it does have some stimulation to it because it’s a threat – you’re stimulated by a threat, but how long can you continue that? Exercise is great for you, but try holding your arm out with a ten-pound weight on it and hold it for hours and hours. That’s not good for you. It must have been stimulating to be in a boiler factory, in those days when they pounded those things and made a hell of a lot of noise, you know, but just keep that up and you kind out it’s a threat. That’s why it’s a stimulus. But we stimulate them with another kind of emotion, with the kind of stimulus that says, ‘You’re going to be okay.’ It’s the stimulation you get out of a party or a fiesta, or having fresh-killed game. The primitive thing – we all eat again. It’s not a threat, it’s the reverse.”

To illustrate, Hench leads me onto Disneyland’s main drag and entranceway – Main Street, U.S.A.

“The forms of these buildings,” he says, “are locked into old associative forms. The old forms weren’t designed by some person at a desk, an architect – the designers responded to a kind of group dream, a group aspiration. In the same way, a folk song was not written by some guy at a piano. That represents a lot of experience, and no one person can put it down. In a symbolic way, architecture is the same – an old architectural form has those reassurances locked in there. You take a certain style, and take out the contradictions that have crept in there through people that never understood it or by accident or by some kind of emergency that happened one and found itself being repeated – you leave those things out, purify the style, and it comes back to its old form again. It has its old message.

Main Street, of course, has the Victoria feeling, which is probably one of the great optimistic periods of the world, where we thought progress was great and we all knew where we were going. This form reflects that prosperity, that enthusiasm. Walt wanted to reassure people. There’s some nostalgia involved, of course, but nostalgia for what? There was never a Main Street like this one. But it reminds you of some things about yourself that you’ve forgotten about.”

Including, presumably, how small you once were – all the buildings on Main Street are considerably smaller than life.

“Yes,” says Hench, “that slightly miniature style is another kind of reassuring thing. Something very large is threatening, but this looks like you could handle everything. You know, of course, that in Europe the great cathedral builders were sensitive to that. They’d put a door in that matched the scale of the building, but then they’d put a smaller door inside that one, and then another one, and finally they got down to a door you could walk through with pleasure because it was your size.

“Here we have City Hall, and of course the opera house, the fire department. And look” – Hench floats a hand in front of him, tracing the tops of the buildings across the square from us – “there is no jar, your eyes can just flow through there. There’s a harmony, a definite relation there, the buildings know each other. They were produced by the same spirit. The fire department wasn’t designed by some guy who hated the guy who did the opera house. These buildings agree on the rules of the game. And notice these columns.” He turns to point out the slender columns on the façade of a nearby store. “We exaggerate the slimness of the columns – again, for confidence. A building with thin columns knows it’s not going to be attacked. It has nothing to fear. People can respond to this confidence without knowing just where it’s coming from, particularly if it’s not contradicted anywhere. These forms aren’t poverty-stricken. They’re just the opposite. Those buildings over there” – he points to the Penny Arcade, Candy Palace and Sunkist Citrus House – “there’s a great deal of variety there, but they all have a harmony running through them, a single theme. They were considered as a unit, not as individual things.”

A few feet away, a cluster of people surrounds an actor in a Mickey Mouse suit. Hench joins the crowd. “The real marvel,” he says, “is this thing. Mickey Mouse is made up almost entirely of curves, and again that’s very reassuring – people have had millions of years’ experience with curved objects and they’re never been hurt by them. It’s the pointy things that give you trouble. Imagine putting a set of dynamic curves together in a design that has the power that this one does, so that he goes all around the world and no one ever thinks of him as an American import. They give him a name and then it’s a déjà vu experience – they know this guy already. They respond to the curves.”

Hench leads the way toward Tomorrowland. “This park was planned like a motion picture,” he says, “to evolve and unfold in time so that a thread runs through it. There are a couple of contradictions that occur on a rational level. Like having a castle at the end of Main Street. But here we’re calling back the old image of a secured point, a strong place. It doesn’t belong on Main Street, but it does belong at the end of a vista like this. The old cities of the earth clustered around a strong point – in fact, in the early colonies you were fined if you lived too far from the center. They figured that if you couldn’t run to the meeting house in time to help defend the group, you were a menace to the community, so you were fined for living out too far. And I suppose there’s enough left in our blood, we who come from Europe, to know that the castle is the strong point – and a home as well. You know the expression, ‘A man’s home is his castle.’ So, in the end, this castle is Everyman’s home.”

Since the summer of 1977, Tomorrowland has been dominated by Disneyland’s newest ride, Space Mountain, a cone-enclosed roller coaster designed to evoke rocket thrust, weightlessness and other scarifying joys of space travel. The cone’s sweeping curves and sharp upward direction state the space theme nicely, Hench says, and “it’s also a logical shape to put that kind of gravity ride in, because if you start at one point and spread the energy, you inevitably wind up with a cone. And cones are very satisfactory as to scale; they look like mountains. The one in Florida has a disarming way of appearing nowhere in particular – you don’t see the base of it, so it floats. It seems like it’s very far away and in fact it reminds me of Mount Fuji in Japan. It has that same kind of serenity and speaks very much the same language.”

A short stroll later – Hench refers to the interstices between lands as “cross-dissolves,” after the filmmaking term for overlapping scene transitions – we are in the courtyard of the Fantasyland castle. “This, of course, is like the medieval fairs,” Hench says. “The courtyard of the castle, where they would pitch the tends for fairs and festivals.”

The ornate carousel, I suggest, is probably one of the least original rides at the park, and the least subject to improvement. Not so. “You’ll notice that we have all white horses,” Hench says. “They weren’t that way originally, but we painted them. Most children want to ride the white horse, since they’ve learned that heroes always ride white horses. In spite of the story of Black Beauty, a white horse is what you’re suppose to ride to glory on.”

Elsewhere in Fantasyland, the pirate ship and Skull Rock from Peter Pan sit side by side, the ship doubling as a snack bar and play structure, the huge skull providing shade for picnickers. A death’s-head hardly seems an icon of reassurance and well-bring – but, Hench says, “it’s softened by the growth around it and by people eating under it. The ship is odd too, you know – a boat sitting here with its gun trained on you like that.” Does making the marauding vessel into a restaurant domesticate it? “Yes, I’m afraid it does,” Hench smiles. “But just look at the kids, climbing around up there. At one time we had a one-legged pirate on there with a parrot, but he wasn’t quite the guy you would want to have around kids. They didn’t quite understand what the pirate was there for, so we took him away.”

The skull and pirate ship aren’t the only death-related images rendered harmless by the overall design at Disneyland. In Frontierland guns are everywhere – from the large display sign of a musket and powder horn to the long rifles in the shooting galleries. The catch, Hench shouts above the incessant barrage of shots, is that these are “old-fashioned weapons. They’re part of the safe past. Nobody worries about the past, and in a sense nobody worries about the future, because that’s going to be up in space, in the space colonies. It’s today where you have the problem – though in Florida we’re going to have a special pavilion about America and tell about America today, so we are taking on that problem. We have spokesmen for the past – Benjamin Franklin, Will Rogers and Mark Twain – but we don’t have anybody for the present or the future yet. We’ll have animatronic figures of those three men like Lincoln, and those figures speak to you. They have a living presence, as it were. Franklin will tell about what the American spirit really was, how it came here and got started, then Mark Twain will take over for the great expansion, and Will Rogers will sum it up. Those last two guys were kind of iconoclasts; Mark Twain was certainly a balloon-buster if there ever was one, so it isn’t a Pollyanna kind of thing. But we’re backing it up with big images.

For the summing up and the future, that’s a problem. I don’t know who in today’s world sums it up as accurately as the musicians, the young musicians. But who are they? They seem to be a collective bunch, they come and go like flowers, you never know – there’s no one guy. But they seem to distill an essence, the spirit of things today. Most of them are optimistic.”

By now we’ve made our way to New Orleans Square, the fictionalized French Quarter built around Pirates of the Caribbean. “I enjoy this,” Hench says. “I think it tells something about New Orleans, the same way our Main Street tells something about Main Streets. It’s a kind of – oh, I suppose it’s like poetry. It condenses everything down to its essence. This, I think, has caught the essence of New Orleans. Of course, it smells better than the original – they have that heavy humidity there.”

His gaze wanders to the Haunted House. “This is another curious building. I think most people expected us to make a Charles Addams ruin here. That was my first opinion. But Walt said, ‘No, I don’t want a ruin over there- God, I don’t want a ruin anywhere.’ He gave us a whole outline of what ghosts were supposed to do. He said, ‘They’ve committed something or other, and they have to live out their crime, act it out. they need an audience. It’s like the old actors’ home, the Motion Picture Country Home out there.’ He went on the BBC and criticized the British for tearing down all their old houses and thus cutting short the ghosts’ terms of going through their particular crime. He said, ‘We have the best audience in the world, and I hereby invite all your old ghosts that are homeless to come and live with me. I’ve got hot and cold running chills, wall-to-wall freaks.’ Before we got the house built, we had a little place there that announced what we were going to do, and any wandering ghost could come into the office and sign up and secure space. It’s really unlike a haunted house, you know – it’s a nice-looking house and it’s not a grim thing at all. It’s kind of funny, It’s full of amusing gags. And it gives people a relation with even the dead.”

A safe relationship with the dead and the instruments of death – with everything, finally, because the setting, the storyboarding and the harmonious environment replace the kiss of death with the sign of dreams. If the only images present were of funny animals, the mechanics of reassurance would not be effective – it’s necessary to supply threats and disarm them, to defang the worst demons and make a world demonstrably safe for the funny animals to play in. The essential message of Disneyland, Hench says as we walk back toward Main Street, is that “there is nothing to fear.”

In a property ordered environment, he continues, the message is wholly accurate. “Look how people who live in cities have to go somewhere int eh country for vacation, and when that sense of natural order creeps back into their veins, they are quite different people. They talk to each other. When the birds are singing and there are green trees and the sun is coming down, they start to feel open and alive again. In the cities, we’re threatened. We don’t talk to people, we don’t believe everything we hear, we don’t look people in the eye – the whole thing is anti-survival. We don’t trust people. We find ourselves alone. If we keep pulling these blinds down and cutting ourselves off, we die a little bit. I think that explains even those brutal pictures like Jaws. People go in there and it scares the hell out of them, and they walk out thinking, ‘My God, I felt something. I’m alive after all.’ They get an exuberance out of discovering that they’re not dead, that they’re feeling things, and maybe they’ve been in some kind of humdrum thing where they haven’t felt anything like that for years.”

Crossing Main Street, Hench stops and glances toward a group of trees near one of the stores. “There’s something,” he says. “You see those trees? They’ve grown rather large – they’re a little bit out of scale here. I guess we’re going to have to do something about that.”

Very interesting stuff indeed. Thank you for posting this.

John Hench was a devout Hindu which you can find running all through his thoughts on the parks.

You are right, though. No one at WED sat around and thought about this kind of thing before hand, least of all Walt. He even said of his movies that he just made the things and left it to the professors to tell him what he had.

I can read this stuff 24/7. I poured over Fjellman over and over back in the day, and this gets the juices flowing again. One thing, though:

“It’s the stimulation you get out of a party or a fiesta, or having fresh-killed game.”

Um. Wha? You lost me on that one, Hench.

John Hench was a unique flavor in the Baskin Robbins of WDI. I think for a time he was a Mr. Blackwell meets Simon Cowell, then evolved into a gentler, more constructive force that we recall him by. He was very supportive to me and many others, but in previous years I heard he was somewhat feared.

Great stuff. I’m always interested in how Hench looked at things. They both “ring true”, and are unnecessary all at once. Still, to read a master speak about something he had a large hand in is after all more like listening to the teacher teach themselves as they look back at their career… For me that’s what Hench is doing here.

Hench talks about reassurance and I believe he is right, this is not just blather. One reason there is so much debate over Tomorrowland is that is has lost it’s reassurance and hope by tossing it’s credibility and logic. He mentions Main Street being optimistic, but so was Tomorrowland 67.

[…] resource for learning more about John Hench’s design process is the 1978 New West article, “Disneyland is Good for You”, written by Charlie […]

[…] Why Disneyland is Good for you […]