This single quote speaks volumes to explain the devout admiration and fascination so many hold for the works of Walt Disney. It also explains my great love of Fantasia, his studio’s 1940 masterpiece. My interest stems not only from the film itself, but from the underlying concept of the entire project; Fantasia was not meant to be a film unto itself, but rather a constantly renewing experiment in animation and music that would blur the lines between art forms and between what was considered “high” and “low” art. To prepare for this, the Disney studio was planning a stream of exciting new animation to be added to the Fantasia repertoire.

This is another major reason for my fascination with the film; during the creation of the so-called “Concert Feature” there were a number of alternate numbers under consideration for the film and its planned follow-ups, and during the decades since several other approaches to the concept were developed. For someone like myself who is obsessed with “the Disney that never was,” Fantasia is a treasure trove of unproduced material. In some ways this material is unique, as, arguably, if the desire existed it could be developed today and folded into a revival of the project. Many of the ideas are just as good as they ever were, and a simple raid of the animation morgue would provide material for any number of fascinating segments.

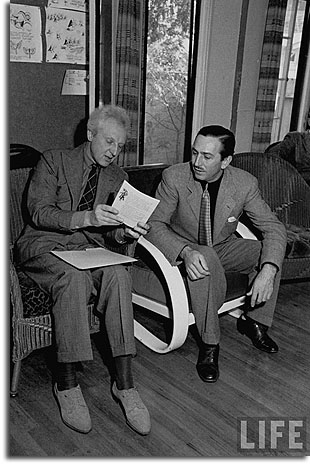

Many of those ideas were discussed in a story meeting for the “Future Concert Feature,” held on May 14th, 1940. Attending the meeting were Walt and conductor Leopold Stokowski, as well as orchestrators Fred Stark and Ed Plumb, arranger Herb Perry, Bill Cox, director Ben Sharpsteen, story man Joe Grant, and Bob Carr, Director of Educational Research for the studio.The discussion begins as the group tries to hammers out a lineup for a full-fledged Fantasia sequel, and ends with an emerging plan to slowly produce new animated segments to rotate in and out of the Fantasia program on a periodic basis. There are enough clues here to help us imagine what a full Fantasia sequel would have been like, though, and as a bit of alternate-universe filmmaking it sounds astounding.

As Sharpsteen explains, the key element in the selection process should be the popular appeal of pieces, or “whether the audience would like them.” Thus, at Stokowski’s suggestion, the film could have kicked off with the Overture from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, which he called “very gay – sparkling – like champagne.” Other numbers Stokowski suggested for the film’s overture included an unspecified Praeludium (“Short and snappy and interesting every second”), although he seems concerned that the piece has been over-played. Also mentioned are Dvořák’s Carnival Overture (“Full of life, full of color and vitality”); Wolf-Ferrari’s Secret of Suzanne (“Gay and fine”); the Overture from Rossini’s Barber of Seville (“Gay and marvelous”); and an unnamed piece by Alexander Scriabin. Rejected were Mendelssohn’s Fingal’s Cave, which he thought too “poetic and gentle for a beginning”; Mozart’s Don Juan which was “a little too tragic”; and von Suppé’s Light Cavalry Overture which is rejected after Sharpsteen points out that it had been heavily “burlesqued” already in the studio’s cartoons. Stokowski rejects an unnamed Brahms piece as “wonderful” but unsuitable, and is concerned that Emil von Reznicek’s Donna Diana “is not so well-known.”

The other serious contender to start off the film, aside from The Marriage of Figaro, was Le carnaval romain by Berlioz. Stokowski seems keen on inserting it into the lineup, although he mentions that he would like to make “a few cuts and repeats” to the piece.

Next in the lineup for this future Fantasia was Peter and the Wolf, which would of course be animated later for inclusion in Make Mine Music. Stokowski speaks glowingly of the piece:

“I think it is top-notch – wonderful music, wonderful humor, wonderful story – I’m all for it. I think it’s the greatest thing Prokofiev has ever done. You can have records of it, but they don’t give you an idea – the records are perfectly played, but the music of course is highly humorous, it’s fantastic and grotesque.”

At this point, Walt enters the meeting and Stokowski catches him up on things:

“Walt, we were talking about the beginning of this concert. We had the overture of The Marriage of Figaro, and in its place we have suggested, for the moment, The Roman Carnival of Berlioz, which is very brilliant and full of contrast, very powerful and interesting.

“I would like to put Peter and the Wolf later in the program; I was going to say in the second half, but it shouldn’t go near Till Eulenspiegel because they have something in common.”

Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, or “Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks”, is a tone poem by Richard Strauss which was to be included in the new Fantasia for the comedic possibilities afforded by its hero, the trickster folk hero Till Eulenspiegel. Said Walt, “I think we can get big laughs out of [it] because of his pranks, surprise gags.”

Walt was also excited about the comedy inherent to Peter in the Wolf, as seen in this quote which really shows how intricately he was planning this project:

“I see us interpreting [Peter and the Wolf] as a highly stylized, caricatured type of thing – the characters would have a certain stylized handling, and the whole thing would be broad caricature – the wolf, all the characters would be like a comic ballet. I don’t mean like a Donald Duck; I mean their movements and everything, like the Ballet Russe might do it. It would be comic, not in the sense of big laughs, but light.”

Stokowski suggests moving Peter and the Wolf to the end of the film’s first half, and asserts that the end of the first half and the end of the film itself are “the two important things to build to.” The first half of the film seems to have been lighter in tone – Stokowski later worries that the second half doesn’t have much humor in it compared to the first.

One of the whimsical segments mentioned for the first half of the film was John Alden Carpenter’s Adventures in a Perambulator. This piece was actually developed by Disney artists, and a reconstruction of its storyboards was presented on the Fantasia Anthology DVD set in 2000. Also proposed was the Polka and Fugue from the 1926 Czech opera Schwanda the Bagpiper. Schwanda, which Stokowski thought “wonderful”, was inserted to the lineup to replace Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, which seems to have originally wrapped up the first half of the film. Ed Plumb points out that with Schwanda, the artists “could go a lot further on the fantastic side than the opera does.” This is opposed to Madame Butterfly which, says Stokowski, “has to be done quite seriously.”

Another segment, which seems to have been planned for the second half of the film, was a selection of four smaller pieces by Debussy. As Bob Carr explained to the others at the meeting, “One of the general instructions Walt gave was to try to get fewer numbers but bigger numbers, and much of the best animated numbers are small.” The solution, then, was to combine similar smaller pieces by the same composer. For this Debussy medley, they selected three tone poems (two of which – Sirens and Sunken Cathedral – are named in the memo) and the third movement of La mer. Carr points out that they’re only using the third movement, saying the first two were “not for us” as they had “no accents to sync animation to.”

A fascinating exchange occurs when Stokowski objects to this plan; while he felt the tone poems were “wonderful”, he also felt that the excerpt from La mer was “awfully difficult to understand.” The rest of the exchange:

Walt: “What’s difficult to understand about it? Doesn’t it sound like the sea?”

Stokowski: “It isn’t clearly done. It’s subjective, like you dream about the sea – it’s not definite.”

Walt: “You said The Rite of Spring was difficult to understand, remember? Maybe we ought to open up on those things instead of playing down to our medium or our public. That’s the very thing we like to have, a challenge.”

There really aren’t enough superlatives in the language to express how I feel about Walt with regards to that quote. It should be chiseled in granite and read aloud before every board meeting or mid-managerial decision. It also illuminates an interesting historical tidbit – that Stokowski had been cautious about the inclusion of The Rite of Spring in the original Fantasia.

Stokowski appeals to Ed Plumb for his opinion on the matter, but Plumb goes with the boss and says that he’s like to see a story done for the segment.

The next piece mentioned is Beethoven’s Minuet in G, although Stokowski feels it doesn’t belong at that place in the program. Bob Carr points out that it had been inserted as a “rest place” between Debussy and the next piece, Stravinsky’s The Firebird, but the general consensus is that Debussy is placid enough without having to take a breather afterward. Stavinsky’s piece was, of course, included as the finale of Fantasia 2000; its abridged version of the 1919 arrangement of the Firebird Suite was much shorter than the version under consideration in 1940, which Walt estimates at thirty minutes in length.

Another piece seemingly on the list for the second half of the film is Bizet’s Carmen. Herb Perry suggests that it could be done humorously to lighten the tone of the second half, and Walt agrees, saying “If we did Carmen I would like to kid it. I mean have beautiful music and beautiful voices, but kid the other angle. Like Dance of the Hours.” Stokowski disagrees again, saying that “it’s such beautiful music, I think you shouldn’t do it that way. I think you should leave it alone in that case.” Walt seems content to leave it at that: “I don’t think we can get it in the first place.”

Also mentioned was Mendelssohn’s Spring Song, which Walt says they can “kid”, and Stokowski suggests Paganini’s Moto Perpetuo (Perpetual Motion) Op. 11 No. 6 (“You could make something very sparkling out of that”) as well as Sibelius’s The Swan of Tuonela. The Sibelius piece would receive a lot of attention from Disney artists in subsequent years, and it too would have its storyboards reconstructed for the 2000 Fantasia DVD. Carr reminds the group that they can make a medley of shorter numbers; Stokowski then suggests Schubert’s Moment musicaux, saying that “the public loves that and it hasn’t been too much done.” He also suggests Brahms’s famous lullaby, the Cradle Song.

Stokowski seems intent on including a Strauss waltz, mentioning them more than once. Walt cautions that The Blue Danube and Tales of the Vienna Woods “were done by a rival outfit, and they weren’t done very well,” so Stokowski says that they’ll just pick a Strauss waltz later. Walt seems similarly determined to animate Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Golden Cockerel, suggesting that “we could stylize the characters; instead of being too human, they would be fantastic.” Later in the meeting he elaborates:

“In the next one I would like to see us do something like The Barber of Seville or like Coq D’Or with good voices, but instead of having to look at the singers themselves we’ll take them, take these beautiful voices, and draw to them. The Coq D’Or gives us more latitude. But I don’t want us to be doing anything with our medium that competes in any way with live action, because the field of fantasy is wide open – it hasn’t been explored, and the others have tried to do it but it just falls flat. So I think we should do the fantastic things.”

Aside from the additional quotable quotes in that excerpt, we can also see that Walt was thinking ahead to the next iteration of Fantasia, and just how far he might have pushed the medium had things gone differently.

With the first half of the film building to Peter and the Wolf, the finale of the entire film would have to be a showstopper to rival Fantasia’s Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria. What was planned would indeed have been spectacular, combining elements of Dvořák’s New World Symphony with negro spirituals. It would have been, in Stokowski’s words, “a very big thing.”

The well-known spiritual Goin’ Home, written by William Arms Fisher and performed famously by Paul Robeson, is based on themes from the second movement of Dvořák’s composition. It would have been arranged for a chorus, and would segue in the film from the second movement (Largo) of the symphony. Said Carr:

“We’ll just develop the spiritual a little further – use the same Goin’ Home motif that is used in the Largo, but develop it further. Go over into the choral, and then go back to the symphony for that last movement.”

It would have been an impressive thing to see. Stokowski estimates that the segment would run about forty minutes, but “we could cut it down to twenty, not counting the spirituals.” Walt cautions against this, giving more insight into how he wanted to expand the Fantasia concept in its sequel and what he had learned from the film’s production so far:

“You wouldn’t have to cut it that much. I think in the present Concert Feature, we have cut some of the things too much. We didn’t know at the time; we’ve never gone that long with anything like that, we were frightened – but I think, with the experience we have had, that we could take a number that would run thirty minutes without any trouble at all, if there is enough variety within the thing itself. I would want to take one of Wagner’s things and try to take it, as it is, for thirty minutes.”

The historic moment in this 1940 meeting comes when Walt suddenly proposes an idea that would change the plans for the “Concert Feature” considerably. After Stokowski expresses concern about Schwanda the Bagpiper and The Firebird being included on the same program, Ed Plumb wonders similarly if Peter and the Wolf and Till Eulenspiegel should be separated in favor of including one each in other future features. This is when Walt drops a bomb:

Walt: “You know, this is just a thought, but we might just take one number at a time – say, make one or two musical numbers a year. Then we can run it with the first Concert Feature. We might run the first Concert Feature the second time, only this time we’ll have, say, Till Eulenspiegel, or Clair de Lune, and we would keep adding to it and changing the program, just like the Ballet does.”

Stokowski: “So people would go twice in one week…”

Walt: “They’d want to see their favorites again, and then we’d have one or two new numbers. It’s something the Ballet has always done. And I see a number I like listed, and I go back to see it again – it’s never changes; the same scenery, the whole thing.”

This is an interesting peek into Walt’s cultural awareness, and his apparent love of the ballet. It’s also a now somewhat poignant look at how he thought this film would be received, and how it would continue to live as something that people would continually revisit. I wish he had been right about that; perhaps if more theaters at the time had been able to accommodate the Fantasound format, things would have been different.

Walt mentions Debussy’s Clair de Lune as a piece they could swap in to the Fantasia program, and it eventually was animated as the first planned addition to the film after its release. When hopes to continue Fantasia faded away, the completed animation was re-edited and re-scored for the Blue Bayou sequence from 1946’s Make Mine Music. A restored version of Claire de Lune was released as a short subject in 1996, and included on the Fantasia DVD in 2000. Walt suggests an innovative (even now!) way to use the piece:

“I thought we wouldn’t open with [Claire de Lune], but later on we’d put it in certain nights – we might even pass out the word that if there’s enough applause at the end there will be an encore, and then if there’s applause they’ll run that.”

Always the showman.

With the new mandate to make piecemeal additions to the “Concert Feature” in lieu of crafting a complete sequel, an idea Walt deems “a more practical approach to the thing,” the team starts to propose segments to be animated. Stokowski asks to retain Schwanda the Bagpiper, New World Symphony, and Peter and the Wolf, as well as The Firebird and the Debussy medley. He continues to push for a Strauss waltz, suggesting Die Fledermaus as a possibility.

Walt expresses a number of considerations for which numbers should be selected, which indicates that he had probably been mulling this decision for some time. One of these concerns was having material that would be appropriate to the available staff:

“I would like to have a group of them to choose from, so that I can move them in according to the way production is moving. For instance I might have a group of men that would be idea for The Sea or Sirens or that combination, or it might be better to start Till Eulenspiegel. In other words we’ll have to record about four of them – that’s the only way to do it – and then we can select from those four the best ones for the plant to work on”

Another consideration was the length of the pieces:

“We want some short numbers and some longer numbers, because one night we might want to replace The Rite of Spring with something of equal length, another night we might want to replace Toccata and Fugue.”

Cost was always an issue too; Walt suggests that The Swan of Tuonela would not only be “swell” but also “very inexpensive for us to do.” He expounds on this later:

“We have to think, too, of numbers that won’t be too expensive to make. For the next year or so, with the market the way it is, it’s probably better for us to take shorter numbers which would be less expensive to produce, and still be effective on the program. I know I could handle Peter and the Wolf in a simple way. I think Till Eulenspiegel we can handle too.”

This is fascinating for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it shows that contrary to popular opinion, Walt wasn’t completely oblivious to budgetary issues. Considering that this meeting was held in 1940, well before America’s entry into World War II but after European markets had started to vanish, Walt’s concern was somewhat prescient while still sadly over-optimistic. Disney’s financial woes would last far more than a year.

A final consideration for the program was whether or not rights could be obtained for the music suggested; Walt mentions that they already have the music for Till Eulenspiegel and Clair de Lune, while they have “a contact” to get the music for Peter and the Wolf.

At this point in the meeting a number of ideas are pitched. Stokowski suggests Sibelius’s Cradle Song for a short number; he also points out Bach’s Air for G String, saying it would be “good for a restful number.” The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan by Charles Tomlinson Griffes is mentioned, as is his The White Peacock. Stokowski goes on to suggest Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun as well as Ravel’s Mother Goose; for Fire Dance (probably the piece by Manuel de Falla), he asks “Could something be done with flames dancing? It’s wonderful music. You could make a wonderful thing of that dance of flames, smoke, explosions coming out of it.” He later proposes that Rhapsody in Blue “would make a good one,” choosing it over Gershwin’s An American in Paris, but the composition would not be animated until its inclusion in Fantasia 2000. When Danse Macabre by Saint-Saëns is suggested (“It’s a wonderful piece of music; it’s fantasic, it’s satire”), Walt mentions that they could potentially “tie that together with something for an ending” as a replacement for Fantasia’s Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria. Herb Perry brings up a piece by Borodin, saying “There’s something about that Prince Igor that keeps drawing people – that wild dancing in there.”

Other exchanges are simply amusing:

Stokowski: “How do you like the Valse Triste of Sibelius? That’s wonderful music.”

Walt: “That’s the one where she dances with death?”

Or provide the occasional zinger:

Perry: “Do you think the Warner Brothers thing has taken away the possibilities of [Mendelssohn’s] Midsummer Night’s Dream?”

Walt: “No, because very few people saw that, after all.”

Stokowski is enthusiastic about using A Midsummer Night’s Dream, suggesting both the Overture and the Scherzo (Wedding March); Plumb points out that the Scherzo would be ideal, saying that “we could make great things out of it.”

Walt suggests Respighi’s Pines of Rome, pointing out its popularity and that it would be easy to do and inexpensive. Interestingly, the piece would go on to be included many years later in Fantasia 2000. When Stokowski suggests Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Walt brainstorms humorously:

Walt: “I think we could do something funny with all the pictures. That would be good, because people hear it so damn much and they can’t quite imagine it, and we could really show the pictures that the music is supposed to represent. We could do a lot with them. There’s a house on stilts, and a Mr. Goldberg and Mr. Schmoola [sic] – you could do something with that – and the eggs…”

Carr: “Then the gnomes, and the old castles…”

Considering the personnel involved, some exchanges are suitably musicological:

Stokowski: “Do you know this, Ed – this Handel music, Fireworks? Is it good?”

Plumb: “I don’t think it can stand on its own feet. It was done on commission.”

Stokowski: “What’s that piece of music, In An Iron Foundry?”

Carr: “We played that; it’s just screeching, sort of.”

Sharpsteen: “It might fit some subject, though, you know.”

Stokowski: “I was going to ask about Chopin – the night music of his, and the beautiful dances – they’re wonderful things. How do you feel about [Rimsky-Korsakoff’s] Russian Easter? That’s highly colorful.”

Carr: “The odd thing about that is that it doesn’t sound like Easter, and it doesn’t sound very religious. It’s a wonderful colorful piece of music that could go with a story – it’s very gay.”

Stokowski: “Well, religion is gay.”

For those, like me, who are intrigued about anything involving Walt and race relations (or, for that matter, the great American songbook), the following conversation is of interest:

Stokowski: “Stephen Foster’s songs – wonderful; I would certainly do those.”

Walt: “They’re a little over-played, don’t you think?”

Stokowski: “I have never heard them well done.”

Walt: “They had a revival of his stuff here lately. I think the Negro Spiritual idea is good. Bring in some good voices, like Robeson…”

Plumb: “The Hall Johnson Choir would be good.”

When Stokowski asks about Wagner, Carr points out that they’d “made out a sheet on it – all the popular excerpts in a series, with a sort of stream-lined story.” This would have certainly been an interesting project – sections of Wagner’s best work pieced together to tell a narrative.

Carr points out that they have an entirely separate list of suggestions for feature-length projects. These sound incredibly ambitious and intriguing:

“It was the idea of taking a big story, like the Story of Atlantis, and to the different episodes putting movements selected from different symphonies, and run it as a feature-length picture with an entirely symphonic background.”

Stokowski agrees that this would be feasible, adding that “it’s a big idea.”

Carr continues with more feature ideas:

“T. Hee made a suggestion for a feature which would be the whole story of music, the history of music, right up to the present time. We go through all countries, all times.”

This idea would later be explored in a number of projects, notably the Oscar-winning short Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953). Yet another feature suggestion was remarkably similar to a concept Disney was concurrently developing about the life of storyteller Hans Christian Andersen. Disney had started work on the project, which would combine live-action footage with animated fantasy sequences, the year before, and a few months before this meeting had entered discussions with independent producer Samuel Goldwyn about co-producing the live-action segments of the film. The talks for the film trailed off over the years, although Goldwyn would eventually release the Danny Kaye-starring musical Hans Christian Andersen through RKO in 1952. Back in 1940, though, the artists were apparently proposing another biographical film about Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Says Carr:

“Bill Roberts suggested this Tchaikovsky story, a story of his life with his music – it would be some live action, about 10% live action and 90% animation.”

Stokowsky points out, in an amusingly oblique fashion, a problem with this idea:

Stokowsky: “I don’t think his life would be good, but I think his music could be made into a wonderful thing. I don’t think it’s possible to put his life on the screen because of the central feature of his intimate life – you just can’t mention if very well, though they have now this Oscar Wilde play which frankly does so.”

Carr: “Yes, it’s a very debatable thing.”

I’m amazed they even worried about nagging issues in Tchaikovsky’s life; after all, pretty much any Hollywood biography of the era was completely whitewashed beyond recognition. That is, if it wasn’t simply fabricated outright from whole cloth. In fact, I’m rather touched at the implication that any such biopic would be done truthfully.

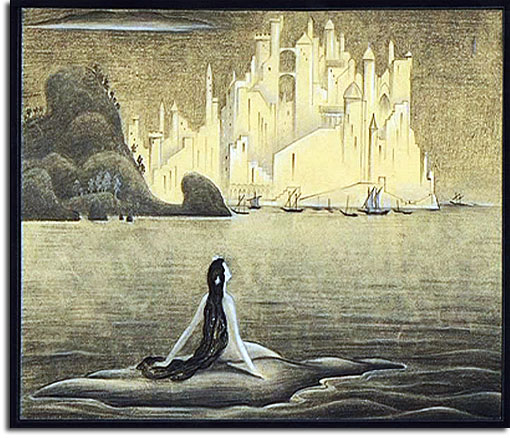

The planned Hans Christian Andersen film would have featured animated segments based on his fairy tales, as can be seen in this 1941 concept art by Kay Nielsen for The Little Mermaid

Another feature idea might sound familiar for fans of Disney theme parks:

“Another suggestion for a feature length picture was what we call tentatively the American Journey; we go geographically over all America, and also historically, and musically we would go all the way from cowboy songs up to Roy Harris.”

Then there’s this:

Carr: “Then another shorter thing would be to take the development of Negro music from real jungle chants, beginning in Africa, through the old slave songs, into spirituals and blues, and finally William Grant Still and a Negro symphony. Do ideas like that seem labored from a musical point of view?”

Stokowski: “No, no – I think they’re very interesting.”

Carr: “Then there was another idea – William Grant Still is here in Los Angeles, and we could commission him to write an African Symphony to fit a scenario that we would lay out.”

Stokowski: “Yes, that could be done, too, and he would do it well.”

This plan not only sounds like a fascinating project, and is an interesting proposal considering the extremely Euro-centric nature of the Disney staff at the time, but it also presages by forty years the planned Heartbeat of Africa show at EPCOT’s designed-but-aborted Equatorial Africa pavilion. Popular entertainment featuring any black performers, songs or culture were rare to begin with in 1940, and it was even more difficult to find those subjects treated with any amount of respect. It would have been interesting to see such a project produced by Disney, who would later hire James Baskett for a project that made him the first black actor to win an Academy Award.

The last suggestion brought up in the meeting sounds more traditional – “a special number on Disney hits in the past” – and it seems funny to consider a retrospective so early in the company’s history. As a more “comfortable” sounding notion, it goes to point out just how bold some of these others proposals were – most of the things mentioned in the meeting the company today wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole. And that’s what really impresses about Fantasia – it’s just as bold today as it was in 1940. Walt was the only one with courage enough to do it then; is there anyone today for whom we could say the same?

I’m similarly impressed by the cultural awareness on display in the meeting. Walt was obviously a brilliant guy but he’d hardly had a traditional education; still, he seems well versed in not only the music itself but the stories behind the pieces. The musical selections the staff mulls cover a wide range of eras and styles ranging from traditional classical music to then-modern symphonic pieces and traditional and modern song.

Few of the ideas mentioned in this meeting would ever come to anything. Some projects were developed further, some even reached the animation process, and still others were revived for Fantasia 2000. But deep in the animation vaults there are still slews of these proposals, just as exciting today as they were then, and hoping against hope to be discovered.

Interesting how this story of Peter and the Wolf clashes with the “official” Disney story as Walt presented it on the Disneyland TV show back in the late 50s, with the story of Prokofiev himself visiting the studio in the 40s during the war (as far as Wikipedia goes, there’s no record of him ever leaving Russia at the time) presenting the idea to Walt of animating it.

As for why Disney knew so much about music, well, to them our ignorance of classical music would be shocking. Music appreciation was a standard part of classroom learning from kindergarten on up, all across the country. We only think it odd because today such education doesn’t exist except in university (and only for those that choose it). There’s also the limits of radio – classical and jazz-pop were the only two genres really being played a lot.

Fascinating, outstanding post. One tiny note: Goldwyn’s production of HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN was released theatrically by RKO in 1952, not by MGM.

B. Baker – Thanks for the correction; I was thrown off because it looks like MGM wound up with home video rights.

Joe – Good points, all. I had not even thought of that Disneyland special when I wrote this! That’s a hilarious point. Obviously he couldn’t have approached Walt at this point, because Walt says that they have a contact to try and get the rights to record it.

Fantasia is my favorite film of all time. I really enjoyed this look at some of the discussions taking place back then. I, like you, would LOVE to have seen some of this take shape. You’re correct, it’s never too late. Maybe now that the princesses are beginning to run their course some bold animation ideas can move to the “front burner.” Who knows? Thanks for this post.

[…] Michael Crawford at Progress City, USA rhapsodizes about Future Fantasias. […]

[…] Future Fantasias, 1940 – Michael Crawford’s report on some of the pieces considered and rejected for animation in Fantasia […]