The Disney documentary train rolls on, with this rather remarkable look at Richard and Robert Sherman – longtime staff songwriters at Walt Disney Productions and composers of some of the best known ditties ever. Much like Walt & El Grupo, The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story is a family affair. Cousins Gregory V. Sherman and Jeffrey C. Sherman have teamed up to tell the complicated and surprising story of their fathers’ lives, which is far from what even lifelong fans might suspect.

The Film

Bittersweet is a word that tends toward overuse due to a lack of alternatives, but nevertheless if you looked it up in the dictionary you would more than likely find this film.

Any Disney fan word their salt knows the Shermans well; in fact, you’d probably be hard-pressed to find anyone anywhere in America that, even though they don’t know the Sherman name, doesn’t know one of their songs. Their body of work is so vast as to be absolutely absurd, and any collection of their music can only really begin to scratch the surface. The Shermans were the staff songwriters at the Disney studio during its most prolific decade – the 1960s – and in that time they wrote for animation, live-action film, theme parks and pop singles. Their career stretches from Tin Pan Alley standards to 21st century Broadway, and their names and faces have been a familiar and comfortably avuncular presence in Disney circles for fifty years. If the Shermans hadn’t existed, Walt would have had to invent them.

The Progress City Connection: In the studio with Walt, performing There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

The Progress City Connection: In the studio with Walt, performing There’s A Great Big Beautiful TomorrowSo, after all these years of seeing the brothers pounding away at the keyboard together and crafting countless familiar melodies, it came as a shock to nearly everyone when this film emerged and disclosed a remarkable fact – not only did the brothers lead very different and separate lives, but for the last 40 years they have been almost completely estranged outside of their work.

This is astounding for many reasons, not the least of which is that they managed to successfully hide this fact from the public while remaining fan favorites throughout. Most remarkably, though, is that they managed to keep working together with a high quality of output while having precious little to do with each other. Living only a few blocks apart, their families remained rigidly separated in private and in public, and cousins Gregory and Jeffrey Sherman were only reunited as adults before they made this film.

The reasons for this separation are as complicated as they are vague, and if there’s a flaw in this film it stems from this issue. The brothers were always very different people, living separate lives, but it seems that even then there remained some level of contact between the two young families. Only after an event in the late 1960s, during which elder brother Robert Sherman took a break from the partnership – and, indeed, from his family for a few days – did the two households truly go their separate ways. This is obviously still a very painful subject for the participants – even the usually ebullient Richard Sherman – and we never really find out what actually happened and why it was so significant.

One could argue that this has nothing to do with the real reason we care about the Shermans – their wonderful music – and that any further interest is sheer gossipmongering. Nor is it reasonable to root for the filmmakers to aggressively pry for more painful details from the elderly brothers when they’re visibly upset; I certainly wouldn’t care to do it, and I’m not as close to the situation as the interviewers. But if the issue is to be made a part of the narrative, and it really is a point that the film hinges upon, than it would make sense for viewers to have a better idea of why those events cast such a long shadow.

As the term bittersweet would indicate, though, the Shermans’ story is far from tragic. Born into a musical family, the two brothers were showmen from an early age. Their father, Tin Pan Alley songwriter Al Sherman, was an extremely prolific and successful composer in the early 20th century. At first the brothers seemed destined for different paths; older brother Robert was far more serious and literary, with ambitions to write the great American novel. Younger brother Richard was the first to dabble in the musical realm, and unlike the more reserved Robert he remains a font of constant motion, thought, and activity. As commentator Bruce Gordon points out during the film, the only real analogue to the two could have been if Lennon and McCartney had themselves been brothers.

The film charts the early lives of the two, through youth and beyond as Robert joins the service and witnesses the horrors of war; the trauma of his injuries, and the sights he encountered while liberating Nazi death camps, are evident even today. Economic necessity eventually forced the brothers into sharing living quarters, and with the encouragement of their father they slowly began to embark on a life as songwriters. Success came fairly quickly, but when one of their songs, Tall Paul, became a hit single for Annette Funicello in 1959, it led to career-defining staff positions at the Disney studio.

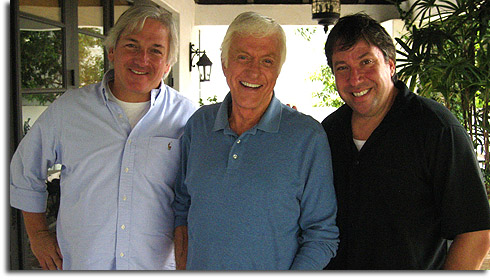

Directors Jeffrey Sherman (L) and Gregory Sherman (R) flank everyone’s favorite funnyman Dick Van Dyke

Directors Jeffrey Sherman (L) and Gregory Sherman (R) flank everyone’s favorite funnyman Dick Van DykeI could go on at length recounting the tales of the Shermans, as this film really does seem like an endless stream of amusing or interesting anecdotes about the brothers and their work. As I always do with any good documentary, I feel like this could have been expanded into five different films and I would have been satisfied. An endless stream of commentators, historians, and participants appear to help tell the stories and discuss the music; off the top of my head, participants include Roy E. Disney, Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, Jeff Kurtti, Bruce Gordon, Leonard Maltin, John Lasseter, Angela Lansbury, Hayley Mills, Leslie Ann Warren, John Davidson, Debbie Reynolds, Alan Menken, John Williams, Randy Newman, John Landis (!), Kenny Loggins (!!) and Ben Stiller (!!!). And that’s just off the top of my head.

The real joy of the film, of course, is seeing the brothers themselves, in both new interviews and a wealth of archival film. Richard remains as sunny and energetic as always, banging away on his piano in his stream-of-consciousness fashion. He also has a seemingly infinite recall of every number the brothers ever wrote. Robert, having moved to London after the death of his wife, remains pensive and at times almost haunted; he focuses now on his career as a painter. Still, despite their occasional barbs and bristles, the footage of the brothers working together remains endlessly entertaining and one gets a hint of the sheer creative energy that must have been a constant presence in the Disney studio of the 1960s.

The DVD

Mercifully, the documentary hits DVD with a suite of interesting extras that flesh out the story of the film.

Video & Audio

Another documentary, another variety of source materials. The newly-filmed interviews consist mostly of “talking head” segments, but the film also extensively uses archival photo, film, and video to flesh out the tale. These are, naturally, of varying visual quality but everything looks pretty good except for elements that were obviously filmed on video in the 1980s.

The film is in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, with audio in Dolby Digital 5.1 (English) and Dolby Digital 2.0 (Spanish).

Bonus Materials

The extras on this disc fall into two main segments. Eight extended segments focus on certain topics with more detail than in the film itself. Then there’s the “Sherman Brothers’ Jukebox”, which features eight individual segments focusing on specific songs. Of special note here is a collection of hilarious sketches that Disney storyman Roy Williams used to slip under the brothers’ office door to illustrate whatever the brothers were up to at the time.

Features

- Extra Scenes – Why They’re “The Boys”, Disney Studios in the 60’s, Casting Mary Poppins, The Process, Theme Parks, Roy Williams, Bob’s Art, Celebration

- Sherman Brothers’ Jukebox – Chim Chim Cher-ee, Feed the Birds, There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow, Jolly Holiday, Up, Down and Touch the Ground, A Spoonful of Sugar, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, Ugly Bug Ball

In Summary…

The Boys: The Sherman Brothers’ Story would seem to be a natural for any Disney fan who has ever hummed a Sherman tune; that would be, well, pretty much all of you. Two very interesting and very different individuals managed to live separate lives while maintaining a public facade that cloaked their personal acrimony, but in this time they also achieved unheard of professional success; during their thirteen years on Disney staff alone they received four Oscar nominations for their more that 200 songs. All told, their work graced 27 Disney films and two dozen television productions, and their post-Disney work includes such family standards as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Charlotte’s Web. It’s a remarkable body of work by two remarkable people.

Recent Comments