“Hello?”

“Hi Herb, it’s Bill Cottrell. We’re over at the Studio working on something and Walt wants to talk to you.”

“Well, OK…”

“Hiya Herbie, it’s Walt!”

“Well hi, Walt, how are you?”

“Fine, Herb, fine. Now listen. I’m over at the Studio…”

“Gosh, Walt, it’s Saturday and you’re working?”

“Yes, Herbie, it’s my studio and I can be here anytime I want! Now tell me – how long would it take for you to get over here?”

“Well Walt, if I come in the clothes I’m wearing it’ll take fifteen minutes, but if I need to shave, get cleaned up and change clothes I’ll be half an hour.”

“Never mind that – just come as you are. I’ll be out front waiting.”

Now, obviously, that’s not what happened verbatim. But it is the general gist of a certain phone call that was made around ten in the morning on September 26th, 1953 – a phone call that would change the Disney company and the entertainment industry forever.

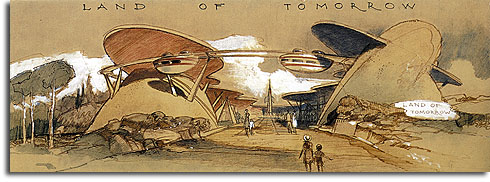

This concept for the unbuilt Liberty Street area was painted by Ryman in 1956; while this Disneyland expansion was never realized, it would inform the design of later attractions such as the Magic Kingdom’s Liberty Square and the also unbuilt Disney’s America park.

This concept for the unbuilt Liberty Street area was painted by Ryman in 1956; while this Disneyland expansion was never realized, it would inform the design of later attractions such as the Magic Kingdom’s Liberty Square and the also unbuilt Disney’s America park.Herb Ryman was not working at Disney in 1953; after leaving the studio to work on Anna and the King of Siam he had continued at 20th Century Fox, with periods of time devoted to his own art and to touring with the Ringling Brothers Circus. He had helped Walt indirectly, though; the Disney studio had been looking for designers to come work on Zorro and Herb recommended future Disney Legends Marvin Davis and Richard Irvine, who had recently been let go when layoffs swept 20th Century Fox. Now Irvine and Davis brought up Herb’s name when Walt needed a talented artist for a secret and very special project.

Herb hoofed it over to the Disney lot and, sure enough, Walt was waiting out front. They headed over to the Zorro production office, where Davis, Irvine and Bill Cottrell were waiting. Walt explained the situation. He was going to build a theme park. The Stanford Research Institute was doing a feasibility study and site search, and Roy O. Disney was flying to New York on Monday to try and sell the project to the bankers that would underwrite the $17 million project.

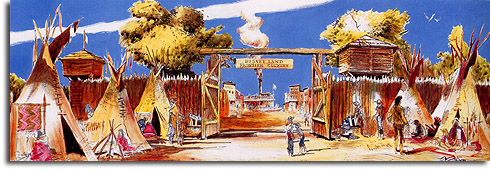

Concept for Frontierland, 1954. Several of the early concept art sketches by Ryman were colored by other artists for use in publicity materials.

Concept for Frontierland, 1954. Several of the early concept art sketches by Ryman were colored by other artists for use in publicity materials.While Marvin Davis had been toiling away for some time on scores of different site plans for the proposed park, Disney and the others knew that bankers would never have the requisite imagination to divine Walt’s grand ambitions from a simple set of layout and plans. To get their intentions across in the most effective way possible, the team knew that they’d need some real artwork – a conceptual rendering of what the park would look like when it was done. If Roy had something visual to present to the bankers, they’d be better able to understand what he was trying to described – a themed environment unlike any other ever attempted.

Herb was intrigued by Walt’s description and said that he’d love to see the artwork that they’d cooked up. Walt looked up, pointed at him, and said “You’re going to do it!”

Herb, naturally, refused.

Wait, what?

That’s right – Herb refused. Throughout his career with the company he was one of the few who could get away with repeatedly telling Walt no, and that’s just what he did here. Ryman was rather irked that Walt would call him up on a Saturday afternoon and expect to have something worthy of being shown in New York on Monday. Herb held himself to an extremely high standard artistically and would not be satisfied with work whipped up on short notice; “You were supposed to be instantly useful and instantly productive and kind of ‘instant genius,'” he would say later. He knew that he would never be satisfied with such a large project if he only had two days to refine it, and so he refused.

“No, I’m not. You’re not going to call me on Saturday morning at 10 A.M. and expect me to do a masterpiece that Roy could take and get the money. It will embarrass me and it will embarrass you.” Ryman, as few others would, called Walt out for waiting so long to ask for his help when he’d known about the project for years: “You know you’ve had this idea for a long, long time. Why did you wait for the Saturday morning before the Monday to come here and ask me to make a fool of myself?”

Herb was serious about his art.

Walt cleared the room.

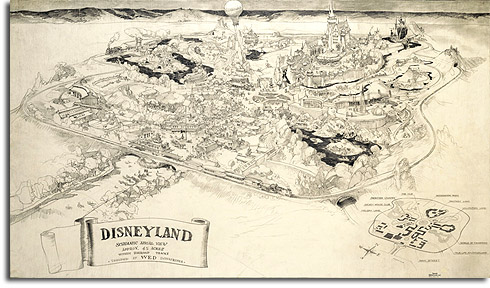

Now at this point, perhaps you’d expect Walt to put on the hard sell. Instead, he paces the room a few times and mulls things over. Ryman would later describe the scene almost as if Walt were a little kid trying to figure out the best approach to wheedle his parents into something. “Herbie,” said Walt, “would you do it if I stay here with you?” Having sensed Walt’s predicament, and after making him vow to stay there the entire weekend to help, Ryman consented. Walt went out to pick up some tuna sandwiches and malted milks, and the two worked nonstop through Saturday and Sunday to finish the rendering. The result was a large pencil sketch, 43″ by 70″, depicting the many wonders of Disneyland.

Thankfully for Ryman, he didn’t have to start with a blank slate. Walt’s desire to create some sort of amusement enterprise dated back to at least 1940, and in the years prior to 1953 the Disney studio artists had created several different plans for parks large and small to be located near the Disney lot in Burbank. Davis and Irvine, along with Harper Goff, had refined the various layouts and concepts into the well-known “hub and spoke” design with a number of themed lands.

This first sketch showed a park far different in layout than the one we know today. Based on a layout by Marvin Davis, it features areas labeled as “Holiday Land”, “Recreation Park” and “Lilliputian Land.” Tomorrowland was the “World of Tomorrow”; Adventureland was “True-Life Adventureland” and was wedged between Main Street and Tomorrowland. The details might have differed but the concepts are familiar; Walt was already insistent on the idea of a train encircling the park, and the Main Street slowly evolved to resemble the Midwestern memories that Disney and Ryman both shared. The early design for the castle, with its massive encircled courtyard, was informed by Herb’s work for 20th Century Fox on The Black Rose. Herb’s drawing, though done quickly and a subject of great dissatisfaction for Ryman himself, was nevertheless loaded with intriguing detail and hints of wonder within. Walt got his money.

Once financing was secured, Walt called Herb up and asked him to come aboard the project in an official capacity. Herb agreed immediately, but let Walt know one thing up front – Ryman would only work on the project as long as it remained interesting to him. As soon as it ceased to be exciting, he’d quit and return to his art. All Walt could do was agree and promise “Well, Herbie, I’ll try to keep it interesting.” He did, and Herb officially became employee #00003 of WED Enterprises.

The stories of Disneyland’s creation, and of Ryman’s role therein, are well-known and too numerous to be recounted here. One contribution, though, I’ll mention. The design for the park’s famous castle had been based on Neuschwanstein, the Bavarian retreat of Ludwig II. Herb was uncomfortable with this, fearing that guests would be familiar with the real-world castle and notice the resemblance. Loitering in the Imagineering workshops while waiting for Walt to make an inspection of some final designs, Herb flipped around the top segment of the castle model so that it faced backwards. The other Imagineers panicked; Walt was on his way, and Herb had just screwed up the model! Marvin Davis and the others told him to put it back the right way, but it was too late – Walt had been eavesdropping and said that he preferred it the new way. So, it stayed.

Ryman continued to work on Disneyland projects throughout the years; some of his best work was for the New Orleans Square expansion in the late 1960s. Full of atmosphere and detail, Herb’s paintings for this new land were true works of art. In 1987, one of his pieces for New Orleans Square was lent to the United States State Department for display in the U.S. Embassy in Paris. It was the first piece of Disney artwork selected for the Department’s Art in Embassies Program.

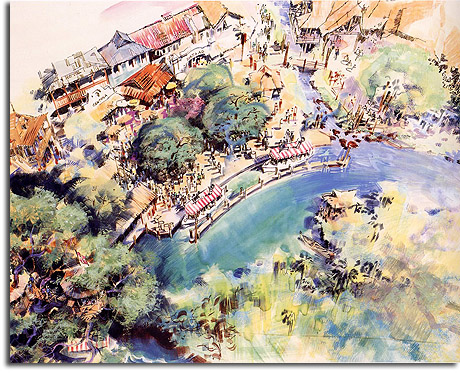

The Square, 1964. In 1987 the original painting was presented to the United States Embassy in Paris for display.

The Square, 1964. In 1987 the original painting was presented to the United States Embassy in Paris for display.The rest of Herb’s Disneyland roster reads like a checklist of important attractions and expansions. The Matterhorn. Pirates of the Caribbean. The New Tomorrowland of 1967. The artwork here can’t begin to hint at the scope of Ryman’s work over the years.

This rarely-seen sketch shows an overview of the 1959 expansion to Disneyland – the Matterhorn, the Disneyland Alweg Monorail, the Submarine Lagoon, and the Tomorrowland Autopia winding throughout

This rarely-seen sketch shows an overview of the 1959 expansion to Disneyland – the Matterhorn, the Disneyland Alweg Monorail, the Submarine Lagoon, and the Tomorrowland Autopia winding throughout This sketch for 1967’s Adventure Thru Inner Space shows the famous Monsanto Mighty Microscope; the Microscope was designed by Ryman and based on an antique microscope that had belonged to his father

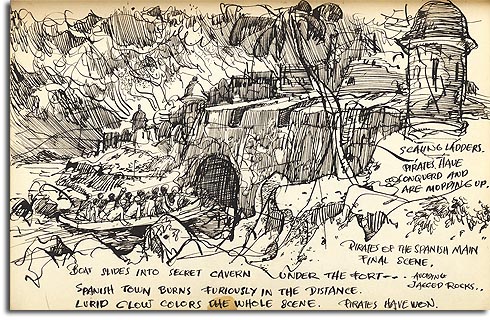

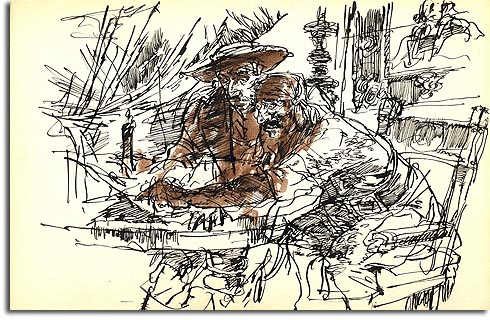

This sketch for 1967’s Adventure Thru Inner Space shows the famous Monsanto Mighty Microscope; the Microscope was designed by Ryman and based on an antique microscope that had belonged to his father Sketch of the final scene for Pirates of the Caribbean: “Boat slides into secret cavern under the fort… avoiding jagged rocks… Spanish town burns furiously in the distance. Lurid glow colors the whole scene. Pirates have won.”

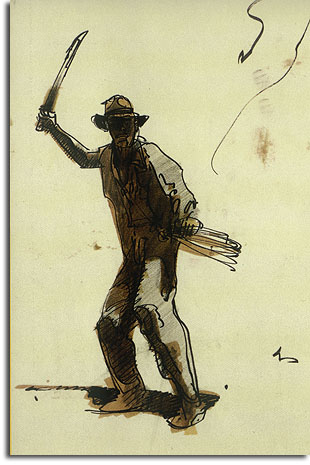

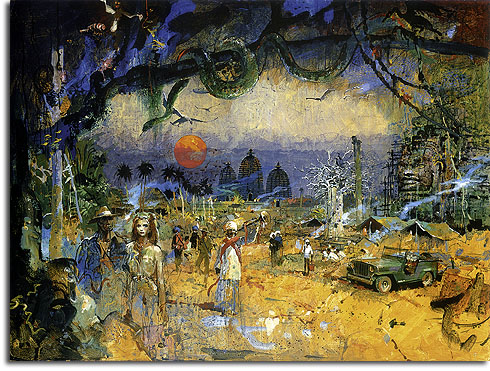

Sketch of the final scene for Pirates of the Caribbean: “Boat slides into secret cavern under the fort… avoiding jagged rocks… Spanish town burns furiously in the distance. Lurid glow colors the whole scene. Pirates have won.”Some of Herb’s last work before his death was on Disneyland projects. He did a number of conceptual pieces for the Indiana Jones attractions proposed for Adventureland, years before the Indiana Jones Adventure actually opened. To think – Herb was at Disney animating classic features like Dumbo and Fantasia in the same years that Indy was having his fictional adventures, and now Ryman was creating art for an attraction based on those times.

While the fictional Indiana Jones was only ten years older than Herb, only Ryman got a chance to work with Disney.

While the fictional Indiana Jones was only ten years older than Herb, only Ryman got a chance to work with Disney.Ryman’s Disneyland career eventually amounted to more than three decades of work, and it all began with that phone call in September of 1953.

Another great piece. I had the honor to work with Herb on Indy, and one day Michael Eisner entered the large conference room at WDI that was littered with art of all the projects in development. The painting you post of Indy was there as well. Eisner was mid sentence when he saw it and stopped, stunned by how Ryman’s work had stood out, and blurted “Who did THAT?”

As to that first, overall concept of Disneyland, which Walt and Herb toiled over that weekend, from my biography, “Warp and Weft: Life Canvas of Herbert Ryman”:

“The needed drawing was now done. Thing is, why would a paper of such importance, be simply rolled, and handed to Roy, when Walt had always been one to successfully, present a pitch? Everything rode on a deal being made; and his brother, of facts and figures, was not exactly personality plus. He didn’t even -like- the idea of a park.”

The simple question that has never been asked by any historian, other than myself, is, “Why didn’t -Walt- go to New York?” Disneyland was the big dream; and as everyone knows, Walt was the consummate salesman.

“Why didn’t -he- go?”

It was for love of Lillian.

It has been said, that Walt was unwarm to his wife; a setting of interests, dead center. But as I explain in my pages, by letting his brother be in lead with great deed, proves that untrue.

For love of Lillian, he let -everything- be put on the line.

This series has been fascinating to me. There was so much going on I never knew about. Keep up the good work.

Thanks very much!

John – I loved that story because it both raised and answered a very good question that I had never thought to ask – why didn’t Walt pitch the park? I had never considered it at all, but when you point it out it seems so strange that Walt would skip such a truly critical meeting that depended so much on selling the project that he knew best.

[…] the architecture of Versailles and Loire Valley chateaus as sources for the castle’s design. Popular legend, however, has it that chief designer Herbert Ryman drew heavily from Ludwig II’s Bavarian […]

I just discovered this series, and am loving it. My husband has been looking for a poster/print of the Herb Ryman 1953 Disneyland concept sketch for years. Any idea where he could get ahold of one?

That’s a great question, and I have no idea if Disney has ever sold reproductions. I’d recommend emailing them and suggesting it! That would make a great poster.

A large, limited-edition serigraph print of the Disneyland concept was once produced, but is difficult to find…but a poster, from the Disney Gallery opening, is often on offer on a well-known, internet auction site.

Fantastic! Thanks, John. I hoped someone would know.

I need to look for one of those posters…

My Dad was a friend of Herb Ryman. I can’t remember that much about what my Dad said about Herb. My Dad was also named John Wells. My Dad made the hall of fame in selling life insurance with Equitable Life Company.

My Dad attended Millikin University in Decatur Il. In fact my Dad played football with George Musso, at Millikin. George became a NFL hall of fame player with the Chicago Bears. My Dad played against President Ronald Reagan when Millikin played Eureka College I believe around 1930. Millikin won that game. My Dad told me that Herb designed Disney Land. I have been to Disney Land three times. I am in the Promotional Advertising business as a salesman with Geiger. I wrote to Herb to see if I could sell products like calendars, pens, magnets, etc. Herb wrote back to me. Then said that the Disney organization allready does business with a company for Advertising promotions.

One more connection with the Disney organization. My wife’s cousin is Bonnie Hunt, the commedian actress. Bonnie plays a voice of one of the cars, in Cars II that has just come out. Bonnie was also in the first movie Cars. Thank you very much for your time!

Micheal, I keep coming back to these pages. They are wonderful!

[…] recently discovered the fantastic artwork of Herb Ryman, a Disney artist who made amazing paintings of Disney parks (both conceptual and realized). His art […]