The adventures that Herbert Ryman had in his world travels were translated into paintings and sketches, which helped him get his position at Walt Disney Productions. But after eight years with Disney, those same travels would lead to Ryman’s departure from the Mouse House.

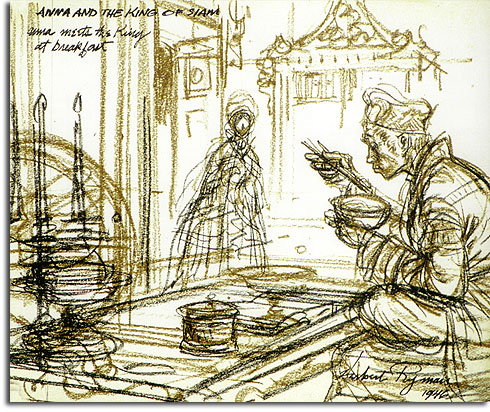

20th Century Fox was developing a film based on Margaret Landon’s 1944 novel Anna and the King of Siam. The film adaptation, starring Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison, was looking for artists with experience in Asian design; at the same time, Fox was facing labor issues within its own art department. While Herb’s experiences in Siam might have made him a natural choice to bring in to work on the film, another fact made the match of man and project too perfect to refuse. In his Oriental adventures, Ryman had become friendly with not only members of the Siamese royal court, but with Landon herself. His close friendship with the author, herself the basis of the eponymous “Anna” of “Anna and the King”, sparked his interest in the project.

Ryman, as had been mentioned, had something of a unique relationship with Walt Disney. They were friends, not merely colleagues; in all his years at the studio, Herb never had a contract. He would come and go as he pleased, and so it was that when he decided to go to Fox to work on Anna he merely went to Walt’s office and said he had to leave. Walt, as time will show, certainly bore no grudge, and he and Ryman remained friendly while Herb was away. In fact, and unbeknownst to Walt, the temporary loss of this valuable artist would pay off in spades in the long-term. It was, after all, at Fox where Herb was to meet many designers that he would help recruit later to build Walt’s first theme park.

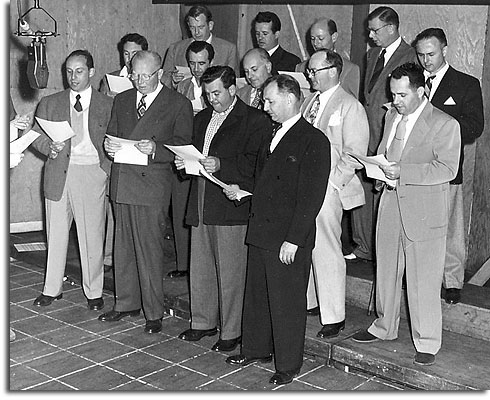

In this photograph of the 20th Century Fox art department are several individuals that would eventually prove crucial to the development of Disneyland and Walt Disney World. On the back row are Richard Irvine (3rd from left) and Marvin Davis (5th from left). On the second row, far left, is Ryman, and beside him is George Patrick.

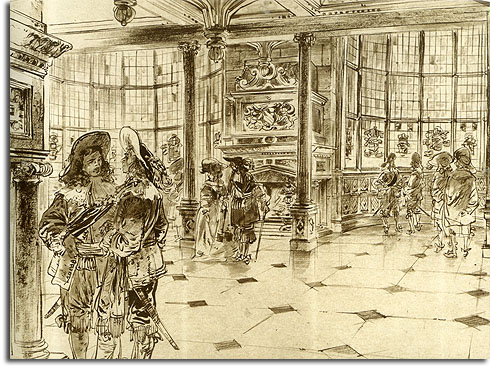

In this photograph of the 20th Century Fox art department are several individuals that would eventually prove crucial to the development of Disneyland and Walt Disney World. On the back row are Richard Irvine (3rd from left) and Marvin Davis (5th from left). On the second row, far left, is Ryman, and beside him is George Patrick.At Fox, Herb worked on a number of pictures including Forever Amber, Down to the Sea in Ships, David and Bathsheba, The Black Rose and The Robe. These lushly produced films gave Ryman something to sink his teeth into, with period settings that allowed him to turn his set and story sketches into truly illustrative pieces of art. The elaborate nature of these films kept him busy, too – such detailed scenes required far more pre-visualization than a typical picture.

While he was at Fox, Ryman continued his personal artistic endeavors. In fact, this is a noticeable thread throughout his life – no matter where he was working, or what he was doing, he still took his private art very seriously. While he certainly made the most of any assignment he was given on a commercial basis, his free time was devoted to his own self-expression though his watercolors and oil paintings.

Herb’s time at 20th Century Fox would prove fruitful, not only for his work but for the contacts he would make. Because, after some time spent running away with the circus, Ryman would get a very unexpected and unique phone call. A request for a weekend of work that would change the world forever.

What I appreciate most about the sketches you’ve chosen to post, is the depth of intelligence you see in the architecture Herb suggests. His slightest scrawl hints at his accurate visualization of how classical moldings work and that they fall in just the right places. He commits to his vision in the simplest of ways. Herb’s uncanny sense (like De Cuir) tells him to mimic the silhouette of a palace and dance the ins and outs of Rococo like a master. We in turn feel that reality because he has no doubt spent hours in the real places cataloging the detail. His sub conscious just guides him to the reality that each stroke conveys. Thanks for posting.