This is our 200th post here at Progress City, and I wanted to do something a little special to mark this milestone of my unexpected commitment. Something from the Bicentennial would be appropriate, I thought, but those seem like they were pretty depressing times so I decided to skip it. Instead we’re going to feature some rarely-seen artwork from Port Disney, the abandoned Disney project that was developed for Long Beach, California, in 1990-91. It’s exciting to be able to post these images, so I hope you enjoy our bicentennial post spectacular!

Disney’s Imagineers have focused their efforts on exploring the myths, romance, challenges and mysteries of the ocean – the world’s last great frontier. Both fun and educational, DisneySea would break down barriers between our guests and the sea.

At the rim of the American continent and the Pacific Ocean, DisneySea will be a place of magic and wonder…

The early 1990s were a very active time at Walt Disney Imagineering. Disney CEO Michael Eisner had announced the “Disney Decade”, which involved an unprecedented wave of expansion in the theme parks division. Imagineering had one park – the then-named Euro Disneyland – under construction, and at least six parks (that we know of) in development. Two of these, the Disney-MGM Studios clones for Europe and Japan, are hardly worth mentioning. The other four, however, are each exemplars of WDI design and show what a creatively fruitful period this was at Imagineering. Almost twenty years later, fans widely mourn that only one of these projects – California’s Port Disney and WESTCOT, Florida’s Animal Kingdom, and Disney’s America in Virginia – were ever built.

The reasons for the demise of these grand projects vary somewhat, but still follow fairly similar themes. We’ve already touched upon the story of Disney’s America, as well as the process that led WESTCOT to be downsized and eventually cancelled. Port Disney followed a similar path to oblivion; all the projects met with some initial resistance from a vocal minority which was only compounded when faced by the then-massive hubris of Disney’s upper-level management. By the time public and private support for the parks rallied and various bureaucratic roadblocks began to fall, fatigue had set in at Team Disney. The effort expended on these projects, combined with rising costs and the deepening American economic recession, seemed to dispirit Eisner and began the long period of retrenchment that marked the remainder of his tenure.

What’s frustrating is that, ultimately, there was little to actually prevent Disney from going forward on these projects. There were regulatory hurdles, of course, but members of the Coastal Commission in Long Beach ultimately appeared as willing to play ball as officials in Anaheim or Virginia. It was really the leadership that failed; reliving the story through press accounts, one gets the impression of numerous tactical successes by Disney officials on the ground in Long Beach while the corporate offices in Burbank made one strategic blunder after another. Token resistance was to be expected by those parties that either wanted to protect their own interests or make an example of Disney; executives didn’t help their cause with secretive negotiations and a clumsy attempt to purchase legislative support in Sacramento as a shortcut around the jurisdiction of the less-friendly Coastal Commission. While obviously many watchdog groups proved an annoyance to Disney, and grandstanding legislators seemed prone to ridiculous demands for mitigation, in the end the public was in favor of Port Disney and its obvious benefits for Long Beach would eventually have led to its approval had Disney not opted to build WESTCOT instead.

The various difficulties involved in getting such massive projects off the ground became an easy scapegoat for cowed executives; in a petulant speech to the World Affairs Council of Orange County in November of 1992, Eisner blamed the state’s business environment and environmental obstacles for sinking the park. Eisner used the opportunity to taunt Californians that Disney would build the DisneySea park not in Long Beach but in Tokyo (where, he probably neglected to mention, the entire bill would be footed by the Oriental Land Company). The story was also an implied threat to Anaheim officials – if they didn’t approve $750 million in improvements sought for the resort area, Disney wouldn’t build WESTCOT either. Anaheim eventually pushed through the approvals for WESTCOT and the improvements for the resort area – and Disney built California Adventure instead.

In the end, it was money that killed the Port Disney project. Development in Anaheim required only the approval of the city council, which had long ago been wined and dined into submission by Disney. Building on the coast in Long Beach required local, state and federal approvals; even though Disney had factored the bureaucracy into their scheduling, Anaheim seemed the easier road to take when faced with the option of only building in one site. Disney would have to pay for less infrastructure in Anaheim, and would be saved the $50-75 million cost of restoring various wetlands sites to offset the environmental impact of the landfill required to build the park. A second gate in Anaheim would also benefit from being built adjacent to Disneyland – a situation so sensible that many in Long Beach thought that Disney never really intended to build Port Disney. It was, they claimed, merely a ruse to force Anaheim officials to accept a less favorable deal on infrastructure and zoning. If it was all a feint, it was an expensive one. Disney spent several years and many millions of dollars on the Port Disney project, only to give up when many felt success was still possible.

But let’s pretend that all that unpleasantness never happened, and that Port Disney opened, as scheduled, in 2000.

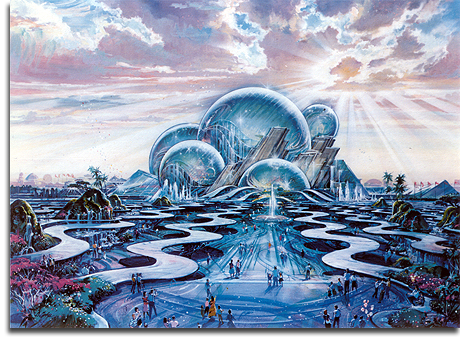

Oceana – the centerpiece of the DisneySea park and the visual icon for the entire Port Disney project

Oceana – the centerpiece of the DisneySea park and the visual icon for the entire Port Disney projectThe Port Disney project began in 1988, when the Disney company finally achieved their long-time goal of purchasing the Disneyland Hotel. The hotel had been built in 1955 by Jack Wrather as a favor to his friend Walt Disney, who at that time couldn’t afford to build the hotel himself. Then-rural Anaheim desperately needed hotel rooms to provide lodging for Disney’s guests, so Wrather filled that role. This later proved a problem for Disney, as Wrather refused to sell the property once Disney could afford to purchase it and a anti-competition clause in their contract prevented Disney from building their own resorts in the area.

After Wrather’s death, Disney took control of the Disneyland Hotel by purchasing the Wrather Corporation outright. They divested most of its assets, save for a few key items. Tangentially, though soon to be relevant, one of these properties was the rights to The Lone Ranger. They also retained Wrather’s interests in Long Beach, which included a 66-year lease on the retired ocean liner Queen Mary. The lease also included an adjacent 55 acre parcel of land, site of a domed building containing Howard Hughes’s fabled Spruce Goose, and the right to fill in and develop 250 acres of water.

Disney immediately began to consider development possibilities for the site. Their interest was not with the Queen Mary, which had proven to be a costly drain on the city since its arrival in 1967. Instead, Disney was looking to develop the property next to the ship. The planning process continued for several years in secret, with only occasional hints leaking out as to what this “Disney-by-the-Sea” complex would be.

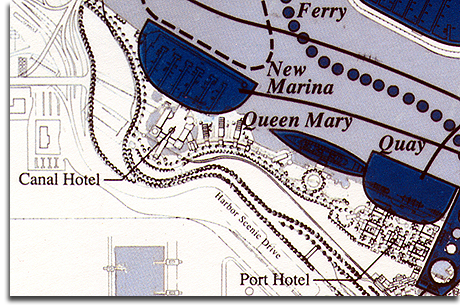

The land that would become DisneySea. Expansion would require 250 acres of landfill, and the removal of the Spruce Goose, Londontowne development, the Viscount Hotel and Adolph’s restaurant, the Reef Restaurant and Cannon’s restaurant.

The land that would become DisneySea. Expansion would require 250 acres of landfill, and the removal of the Spruce Goose, Londontowne development, the Viscount Hotel and Adolph’s restaurant, the Reef Restaurant and Cannon’s restaurant.In early 1990, Michael Eisner disclosed that Disney intended to build a second theme park in Southern California. The new attraction would be built in either Anaheim or Long Beach; with typical Eisner charm it was announced that the decision “depends a lot on which one wants us more.” In July of that year, Disney was forced by the terms of their development deal to disclose their plans for Long Beach. They were nothing short of spectacular.

The $3 billion Port Disney resort complex would span roughly 414 acres on both sides of Queensway Bay. The two sides of the resort would be connected by watercraft, monorail and the Queensway Bridge, crossing the bay on the west side near the mouth of the Los Angeles River. The resort as announced would contain the 225-acre DisneySea theme park, a cruise ship port, and five – later six – resort hotels that would total 3,900 rooms over 125 acres. The entire area would have integrated design elements typical of a Disney resort, including landscaping, signage and transportation. The two main areas of the resort, divided as they were by the Bay, were designated the City-Side and the Port-Side.

City-Side

The City-Side would contain many of the resort’s hotel, shopping and entertainment areas. Described as the “urban recreational” part of the resort, it would also provide public access to the waterways and allow the resort’s transportation system to connect with the regional light rail Blue Line.

This part of the development would be integrated with several existing facilities, including the Hyatt Regency Hotel, the Long Beach Convention Center, Shoreline Village and the Downtown Long Beach Marina. The Disney-built hotels in this area would be linked by an internal lagoon system, and hotel-adjacent Shoreline Drive would be redesigned to be more pedestrian friendly. Port Disney’s monorail system would run alongside Shoreline Drive, connecting the three City-Side Disney hotels before turning southwards towards DisneySea.

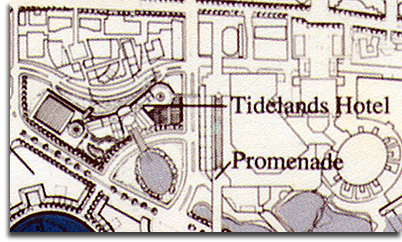

Tidelands Hotel

Described as “first-class” and bounded by Seaside Way, Pine Avenue and Shoreline Drive, the 900-room Tidelands Hotel would connect by pedestrian bridge to the Convention Center and The Pike at Rainbow Harbor, a retail and entertainment development. Set on a 14.8-acre lot, the hotel would be built above a series of parking garages and conference space.

Originally designed with a six-acre park and pond, as shown above, its layout was altered in early 1991 in response to public pressure. Some residents disliked the design, saying it “faced away” from downtown, and suggested the hotel be moved westward. Disney agreed, and reconfigured the site by moving the hotel to the west and extending the water feature along the entire eastern border of the property. Possibilities under consideration included a freshwater pond or a connection to the existing Shoreline Aquatic Park lagoon to the south. Disney planned to coordinate with the developers of the then-unbuilt Pike property to the north to ensure that sight-lines to the ocean remained clear.

Shoreline Hotel and Retail/Entertainment Center

This 25-acre site would contain the 400-unit, all-suite Shoreline Hotel and feature a variety of shops, restaurants and entertainment along a boardwalk on its ground floor (in fact, it sounds quite similar to the later Boardwalk Resort at Walt Disney World). The hotel would wrap around the northern shore of the Shoreline Aquatic Park lagoon, providing access along the boardwalk to “paddle boats and other non-motor craft.” Disney later considered expanding this lagoon as well.

The construction of this hotel would replace the northern section of the Shoreline Aquatic Park, eliminating a 70-space R.V. campground. In May of 1991 Disney agreed to replace those facilities with a similar campground on the east bank of the Los Angeles River.

The Shoreline Hotel would also house a ferry landing that would connect the City-Side of the resort with the WorldPort and DisneySea across the Bay.

Shoreline Aquatic Park

The existing park in this area would remain, providing continuous public access to the waterfront. A long promenade would extend the length of the development, with landscaped parks and fishing facilities.

Marina Hotel

Set on a 20-acre lot east of the Convention Center, the 700-room Marina Hotel would connect by landscaped walkways to nearby hotels, the Convention Center and the existing downtown marina.

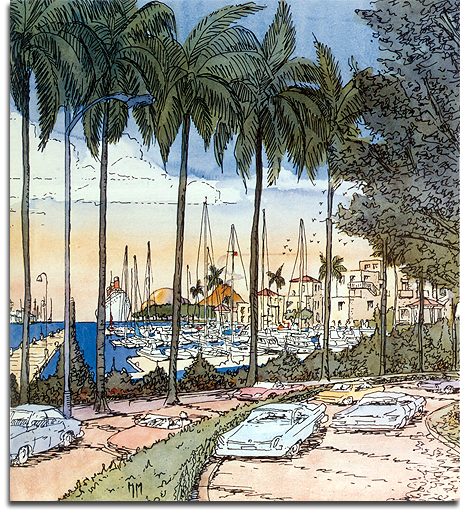

“Grand Entry” – Guests catch their first glimpse of DisneySea as they turn on to the entry drive under the Queensway Bridge looking southeast. The Canal Hotel is to the right.

“Grand Entry” – Guests catch their first glimpse of DisneySea as they turn on to the entry drive under the Queensway Bridge looking southeast. The Canal Hotel is to the right.Port-Side

The project entry should create a sense of anticipation upon arrival, evoke the waterfront resort feeling, and add a touch of fantasy.

As guests crossed over the Queensway Bridge or drove along Disney’s own access road, they would enter “fantasy-resort” Port-Side. Access was available by car, ferry, monorail or pedestrian bridge, and guests would pass two hotels, a guest marina and the WorldPort before arriving at the jewel of the resort – DisneySea park.

Canal Hotel

The largest of the Port Disney hotels, the Canal Hotel would house 1,400 guests rooms on a 45-acre site “encircled by a ribbon of water.” The hotel would have a 2,300-space parking lot and a 150-slip guest marina.

These plans changed in May of 1991 when the Canal Hotel was redesigned; a new, smaller layout was announced and the hotel was moved slightly to the east. This alteration to the plan made way for a new, sixth hotel. Disney designers felt that having three hotels on the Port-Side instead of two would allow for smaller, five- to seven-story buildings that would provide a more consistent resort aesthetic.

It is most likely the Canal Hotel that was designed to resemble Long Beach’s old Virginia Hotel.

The Port-Side Hotels in 1990. The Canal Hotel would eventually be downsized and moved to the east to make room for the Regatta Hotel

The Port-Side Hotels in 1990. The Canal Hotel would eventually be downsized and moved to the east to make room for the Regatta HotelRegatta Hotel

The sixth hotel in Disney’s plan, the Regatta was to take the place of the Canal Hotel when it was reduced in size and moved closer to the Port Hotel.

Port Hotel

The 500-room Port Hotel would have 800 parking spaces, and its 20-acre site would be “crisscrossed by ‘finger canals.'”

WorldPort

The WorldPort, situated on the doorstep of DisneySea park, would serve as the nervous center of Port Disney. Cross-channel and excursion ferries would depart regularly, and a waterfront promenade would provide access to shops and restaurants. Dockside entertainment would help create an active port atmosphere; Disney-controlled water and the port plaza would be home to “theme boats, pageants, and special events.” Water ferries would provide service to Avalon, Newport Beach, Dana Point, Redondo Beach and Marina del Rey. The WorldPort would also serve as the southern terminus of the Port Disney monorail line.

This is also where the Queen Mary would be docked, as initial Disney plans called for the ship to be moved 700 feet from its current location to sit between the Port Hotel and the WorldPort quay. The actual disposition of the ship in Disney’s plan remained nebulous throughout the development process; Disney insisted the ship was an “important visual icon” for the resort, but claimed that they didn’t know what they would do with it.

The ship, already converted to a hotel when Disney took over its lease in 1988, was a consistent money loser but had many supporters in the community. The city, having already leased the ship to a number of unsuccessful parties, dumped control of the hotel on the Harbor Department in 1978. Desperate to relieve themselves of the financial drain, they leased the Queen Mary to Wrather – and subsequently Disney – in 1980. They attached one clause: if Wrather, or later Disney, wished to back out of their long-term lease, they would be forced to purchase the ship from the city for its scrap value and then pay to have it scrapped or scuttled. The city didn’t want the Queen Mary back – if Disney didn’t want it, the ship was dead.

This naturally upset many of the ship’s proponents, who argued in favor of preserving its classical beauty and art deco ambiance. Disney still refused to commit to the ship’s role in Port Disney, and after the resort project fell through many feared the worst. Disney divested themselves of the ship in 1992, but after a brief closure it reopened. Despite many attempts to rid themselves of it, the graceful ocean liner still graces the port of Long Beach.

An ironic footnote: Long Beach officials have longed to rid themselves of the Queen Mary for years, but when it came time for Disney to construct Tokyo’s DisneySea park they built themselves their own copy – the “S.S. Columbia” sits in that park’s American Waterfront area.

Model of Port Disney, with the DisneySea theme park. The cruise ship terminal is located in the immediate foreground.

Model of Port Disney, with the DisneySea theme park. The cruise ship terminal is located in the immediate foreground.The Cruise Ship Port

At the southernmost tip of the resort, a five-berth port would provide cruise ships access to Long Beach for the first time. The terminal, operated by the Port of Long Beach, would have its own 1,500-space parking area and a curving breakwater structure with a 250-slip public marina. The breakwater would also house a landscaped public park, with several fishing piers and an oceanfront promenade that would extend northwards past DisneySea to the City-Side of the resort. Thus, guests could walk or bike from one end of the resort to the other without crossing a road.

These public facilities were crucial to Disney’s efforts in obtaining permits for the resort; the Coastal Commission only allows those facilities that require oceanfront access permission to create landfill, and the Commission didn’t necessarily see a theme park as fitting those parameters. In order to justify the 250 acres of landfill required to build Port Disney, Imagineers loaded the design as much as possible with coastal-specific uses. These included the marinas, the cruise ship port, the ferry ports, and even the aquarium and research facilities at the DisneySea park. While this still didn’t exactly help sway the Commission, and Disney was forced to justify the need for another cruise port in Southern California, necessity proved the mother of invention and helped craft a nicely integrated design for the resort.

The cruise port would offer routes to the north and south along the West Coast of the United States and to Mexico, with possible destinations including Mazatlan, Ensenada, San Francisco, Seattle and Alaska. It would also provide competition for the Port of Los Angeles – in fact, it would make Long Beach the largest cruise terminal on the West Coast.

As part of later redesigns in May of 1991, the cruise port was reconfigured for easier access. The curved breakwater was altered, and the marina area was moved farther to the north.

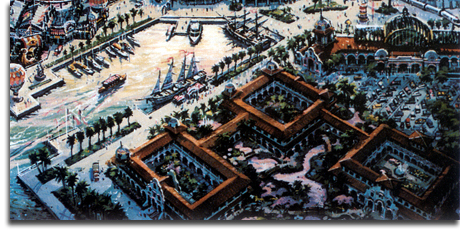

An artistic rendering of the DisneySea theme park. Note that this is one of two different park layouts depicted in renderings.

An artistic rendering of the DisneySea theme park. Note that this is one of two different park layouts depicted in renderings.DisneySea

Last, but not least.

The DisneySea park designed for Long Beach incorporated many elements that might be familiar to fans of Tokyo DisneySea, but also featured many scientific and research-based aspects reminiscent of EPCOT Center’s The Living Seas and some aquatic attractions similar to Florida’s Typhoon Lagoon. Guests would encounter live sea creatures and learn about the oceanic environment, but they’d also experience fantastic environments themed to a Grecian village, an Asian watermarket and a Caribbean lagoon. Imagineers would block views of the unsightly cargo port to the west with a massive, 17,000-space parking garage.

The various ports of call themed to places real and imagined would surround the park’s centerpiece, Oceana. Inside the futuristic bubble-shaped structure would be housed the world’s largest aquarium, “luring guests to a fascinating evolutionary journey through the world’s seas.”

Information on the attractions designed for DisneySea has remained sparse over the years, but we have some clues as to what awaited visitors. Combine these facts with some guesswork based on the eventual attraction lineup of Tokyo’s park, and you might get an idea of what could have been.

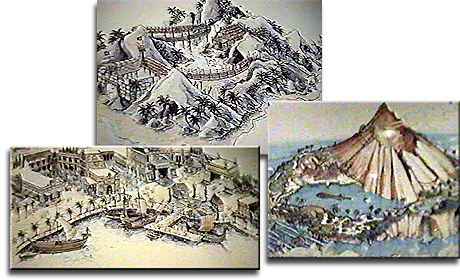

Three possible scenes from Oceana (from top): DisneySea experts care for sea lions, an underwater observation deck, and an exhibit for viewing penguins from underwater (JHM and Imagineering Files)

Three possible scenes from Oceana (from top): DisneySea experts care for sea lions, an underwater observation deck, and an exhibit for viewing penguins from underwater (JHM and Imagineering Files)Oceana

The focal point of the park, Oceana would contain a state-of-the-art, two-story aquarium. Reaching depths of up to 30 feet, the 10-12 million gallon oceanarium would be the world’s largest. Proposed features would include:

Future Research Center – Similar to EPCOT Center’s Living Seas pavilion, the Future Research Center would bring scientists from around the world to conduct oceanographic studies.

Hands-On Exploratorium – Interactive exhibits would allow “adults and children alike” to learn about the ocean and its diverse marine life.

“Clean Sweep” Exhibit – A hands-on exhibit that would demonstrate how to clean up an oil spill.

Submarine Simulation – This attraction would “take visitors on a pretend ride to famous underwater locations.”

Various realms of adventure (clockwise from top): Pirate Island, the Mysterious Island area, and Heroes’ Harbor (JHM)

Various realms of adventure (clockwise from top): Pirate Island, the Mysterious Island area, and Heroes’ Harbor (JHM)Mysterious Island

Sitting in the shadow of a man-made volcano and said to represent the “scary side” of DisneySea, Mysterious Island would center around stories of Captain Nemo and the Nautilus. This area was eventually re-created at Tokyo DisneySea.

City of Atlantis – Guests would discover the lost city of Atlantis on what was deemed “a modern version of a Disneyland ‘E’ attraction.” Could this be a predecessor of Tokyo’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea?

Pirate Island – Publicized as “Tom Sawyer’s Island times 10,” this area would allow children to explore while following clues to buried treasure.

Nemo’s Lava Cruiser – A thrill ride where guests “careen suspended through underground caverns.”

Heroes’ Harbor

Based on ancient legends, this area would be themed as an ancient Greek village. Heroes’ Harbor is where “the myths and legends of the sea come to life.”

Aqua-Labyrinth – Entrance to Heroes’ Harbor would be through the Aqua-Labyrinth, a “challenging maze with walls made only of water.”

Sinbad attraction – Little is known about this ride based on the Arabian hero, although Tokyo DisneySea is now home to Sindbad’s Storybook Voyage.

Ulysses attraction – Another attraction was to center on the adventures of the Homeric hero Ulysses (Odysseus).

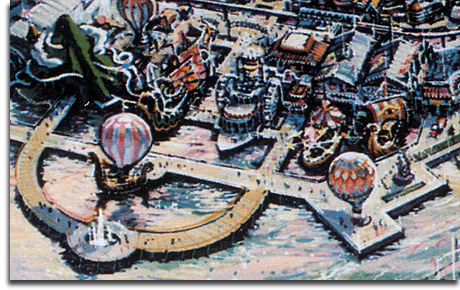

Fleets of Fantasy (JHM)

Fleets of Fantasy (JHM)Fleets of Fantasy

This area seems to sit near the boardwalk area, and renderings depict a number of funfair rides in nautical trappings. According to Disney, “a harbor of fabled and fanciful ships, including outsized Chinese junks and Egyptian galleys, would disguise exciting rides and dining and entertainment experiences.” It’s possible that an outdoor amphitheater was planned for this area.

Boardwalk and Rainbow Pier

As a tribute to Long Beach’s past and the former Pike amusement park and horseshoe-shaped Rainbow Pier, a nostalgic boardwalk would occupy the side of the park facing downtown. Various renderings depict a Ferris Wheel and old-fashioned wooden roller coaster similar to those in California Adventure’s Paradise Pier.

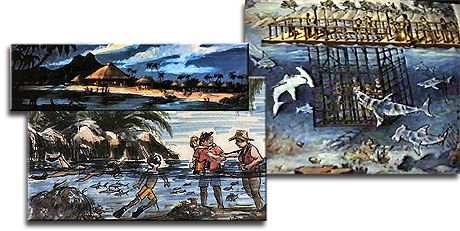

Adventure Reef

This area of the park would be most similar to Florida’s Typhoon Lagoon – not surprising since DisneySea Imagineer Kym Murphy had worked on both that water park and the Living Seas at EPCOT. Focused on actual real-life aquatic activity, Adventure Reef would allow guests the opportunity to surf or snorkel through tropical reefs teeming with fish. It was described as a “paradise” setting in which guests could swim and wade.

Most surprising in this area was an attraction in which guests would be lowered in a steel cage into a tank full of sharks, as seen above.

These images possibly depict the second, downsized version of DisneySea (JHM and Imagineering Files)

These images possibly depict the second, downsized version of DisneySea (JHM and Imagineering Files)During the planning process, Disney developed at least two versions of the resort and its centerpiece theme park, DisneySea. The original design, which called for 250 acres of landfill, did not receive legislative support as easily as Disney had hoped, so in the fall of 1991 they unveiled a smaller site plan. While committing to neither version, and always pointing out that both designs were likely to change before construction, Disney at least had a contingency available should the cost of the larger plan prove prohibitive.

This second plan only required 50 acres of landfill instead of 250, and that area would be mostly used by easily-approved coastal projects such as the aquarium and research facilities. Under this plan, the cruise ship terminal and marina would be built by the neighboring city port, which could more easily obtain the necessary permits and in turn reduce Disney’s need for landfill. The Queen Mary would then be moved from Disney property to the port facility. The existing Harbor Department headquarters would be demolished and relocated to the new terminal site, allowing Disney to occupy its former location.

Ultimately, Disney officials seem to have been displeased with the smaller plan that necessity had forced upon them, and that in part led to the project’s abandonment. Delays in the approval process and escalating cost made Port Disney difficult to justify when compared to the cheaper and quicker yet still spectacular WESTCOT option.

One last oddity: in October of 1991 the name of the resort project was changed from “Port Disney” to simply “DisneySea.” Previously, only the theme park went by the DisneySea name. Officials from the Port of Long Beach objected to the Port Disney name, thinking that it somehow was threatening their identity or prominence. Disney made the concession and changed the name, and two months later chose Anaheim for its second gate in California.

The End of a Long Day

Disney promoted Port Disney as “an 18-hour experience,” yet it probably would have been much more:

The waterfront at night is also exciting. The shapes of the bridge, boats and buildings; the reflections in the river, canals and lagoons; and the City and Port lights illuminate the different character of the nighttime waterfront. In addition, special lighting and special events, such as laser and fireworks shows, boat parades, and evening harbor cruises, provide drama, excitement, and romance to complete the palette of water experiences…

If only.

P.S. Scansafe? Really? So lame. Dear Prudence, won’t you come out to play?

Welcome everyone from Disney and More – feel free to take a look around and make yourselves at home. Thanks to Alain for the link!

[…] The site ‘Progress City’ has just posted their own article on the Port Disney project at Neverworlds Bicentennial Special – Port Disney | Progress City, U.S.A. . The article also brings together a lot of artwork that’s been scattered around the Internet – […]

Amazing. If they’d built that, I might want to go to California.

Wow, Port Disney’s getting a lot of press lately.

Thanks for the info. Some great stuff, particularly the new shots I haven’t seen. As well as the “Lost Disney Sea” article, you might want to go over to Blue Sky Disney, they published an article earlier this month with interesting info as well.

Tee

Here’s the link: http://blueskydisney.blogspot.com/2009/04/what-was-gotten-versus-what-couldve.html

The size and quality of the Oceana and overview paintings are incredible. Thanks for the post!

First I encourage everyone to go read the two other stories linked above. Honor posted his on Blue Sky Disney after I had started writing this (which I thought was a weird coincidence) and I didn’t know about the story on MiceChat until that thread got linked here. That story is excellent, and gives you a far better sense of what DisneySea would have been like on the ground than my piece does. It only makes me more sorry that it was never built.

Future Guy: You are so right. I’ve yet to book a flight to go see DCA, but I would have been there ASAP for DisneySea OR Westcot.

Tee: Thanks! I don’t know why there’s been such a boom of Port Disney talk lately, but I’m glad it’s finally getting some respect. And finding any new artwork from the park is always incredibly exciting…

Randy: You’re welcome! Hopefully more will eventually come to light…

Just curious,

I love all the artwork and perspective from yours, Lost DisneySea and Blue Sky’s articles. Where did you find such detailed maps and concept pieces? Did you have the Port Disney Times by any chance? I was lucky enough to have a friend give me one of the WestCOT brochures that they passed out to people back in 1991. It’s still a shame when I look at it. I can only hope with Lasseter there they wind up creating something grand for the third park. Something closer to the lever of DisneySea.

Thanks again.

I managed to get my hands on a copy of the Executive Summary of the Preliminary Master Plan of the resort, and that’s where my images came from. This was a shorter version of the actual Preliminary Master Plan, which was prepared to distribute publicly to publicize the concept. I would *love* to find a copy of the Port Disney Times, but I’ve never seen one anywhere.

I would love to see a project even close to the level of DisneySea but I don’t know if we ever will again. That trifecta of DisneySea, WESTCOT and Disney’s America weren’t overloaded with “franchise” characters and marketing tie-ins, and I just don’t know if Disney will ever do something truly original like this again. It makes me sad.

Solid blog. I got lots of great data. I?ve already been keeping an eye on fraxel treatments for some time. This?utes fascinating the way it keeps different, yet a few of the core elements stay the same. Perhaps you have observed a lot alter because Search engines created their most recent acquisition within the field?

Hey Michael,

I used this awesome presentation to draw an idealized site plan of the theme park part of Port Disney. If you haven’t seen it, it’s here:

http://www.idealbuildout.blogspot.com/

[…] to town. Here’s the story behind DisneySea. (For more pictures, check out this Progress City post or go to the A&D exhibit, of […]

[…] to town. Here’s the story behind DisneySea. (For more pictures, check out this Progress City post or go to the A&D exhibit, of […]

[…] It’s the perfect ‘locals’ park, and although I know we’ll be back, I really wish Port Disney would’ve been built in Long Beach so we had a closer version of it. Of course, chances are the US version would’ve been […]

[…] come to town. Here’s the story behind DisneySea. (For more pictures, check out this Progress City post or go to the A&D exhibit, of […]

[…] reading posts about Disney projects that never came to fruition in their original forms — Port Disney, WESTCOT Center, Disney’s America, and The SS Disney — and partially because I am just […]

[…] For a really nice in-depth article on the proposed DisneySea in Long Beach, visit our friends at Progress City. […]

[…] http://progresscityusa.com/2009/04/29/neverworlds-bicentennial-special-port-disney/ […]

[…] http://progresscityusa.com/2009/04/29/neverworlds-bicentennial-special-port-disney/ […]