From the day of his birth, 100 years ago today in Vernon, Illinois, Herbert Ryman was never meant to be an artist. It was simply an impractical concept; after all, starving artists never found gainful employment! It would have been far more respectable to follow in the steps of his father, a local doctor. But after the elder Ryman died in the trenches of World War I, and Herb’s mother Cora became the sole breadwinner of the family, the idea of one of the three Ryman siblings wasting their lives with the study of art seemed unthinkable.

Thankfully for all of us, Herb and fate had other plans.

Through a concerted campaign of persuasion, and a bit of good old fashioned guilt when Herb seemed sure to die from scarlet fever, the young artist did manage to dodge a life as medico. After studying at Millikin University in Decatur, Herb managed to escape to the Art Institute of Chicago where he would immerse himself in the fine arts. His natural talents combined with hard work and he eventually graduated cum laude.

Through a concerted campaign of persuasion, and a bit of good old fashioned guilt when Herb seemed sure to die from scarlet fever, the young artist did manage to dodge a life as medico. After studying at Millikin University in Decatur, Herb managed to escape to the Art Institute of Chicago where he would immerse himself in the fine arts. His natural talents combined with hard work and he eventually graduated cum laude.

Herb’s talent was spotted early on; throughout his college years he exhibited his art to great acclaim. But while he obviously had the skill to make a life as a fine artist, the nation was plummeting into the abyss of the Great Depression. The only obvious option for employment after college was in the field of commercial art, but Herb hardly wanted to get stuck in the advertising game. Instead he packed his bags and headed to Hollywood, were more interesting opportunities would most certainly present themselves.

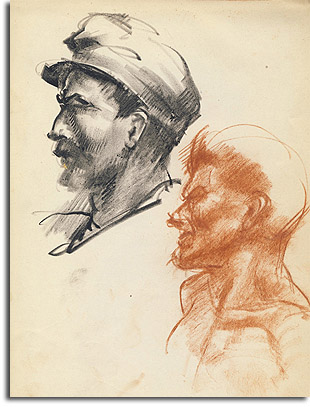

These sketches by Herb Ryman, from his time as a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, provide an early example of his observational skills

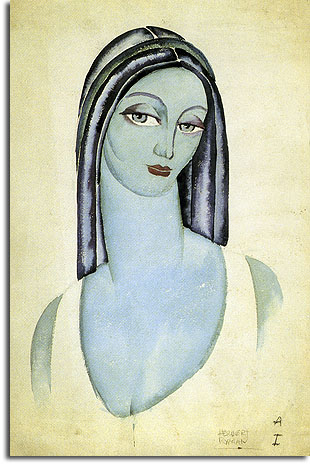

These sketches by Herb Ryman, from his time as a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, provide an early example of his observational skills I find this piece by Ryman, labeled “Portrait of a Blue Lady,” interesting because it’s so unlike his other work. The sleek, simple lines evoke the Art Deco movement. This piece dates to around 1932, while Ryman was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago.

I find this piece by Ryman, labeled “Portrait of a Blue Lady,” interesting because it’s so unlike his other work. The sleek, simple lines evoke the Art Deco movement. This piece dates to around 1932, while Ryman was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago.After a series of adventures, Ryman wound up at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1933, smack-dab in the middle of Hollywood’s golden era. He took a position in the Art Department, working for legendary art director Cedric Gibbons. An early assignment was painting prop oil paintings for the Lionel Barrymore vehicle The Late Christopher Bean. A portrait of Garbo followed, for Queen Christina.

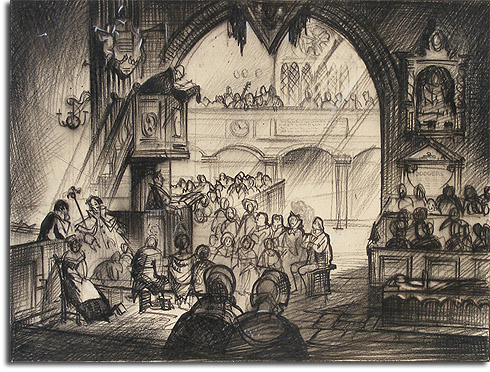

Most of Ryman’s work at Metro, though, was as a sketch artist. He worked on various pieces of conceptual work, creating inspirational sketches for set designs. He worked on layout sketches, and continuity illustrations. He was, essentially, storyboarding these live action features – something that would come in useful later.

Herb worked non-stop at MGM – twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Projects with which he was involved included Treasure Island, China Seas, David Copperfield, A Night at the Opera, Naughty Marietta, The Merry Widow, The Barrets of Wimpole Street, The Last Waltz, A Tale of Two Cities, Lady in Ermine, Rasputin and the Empress, and Tarzan and His Mate.

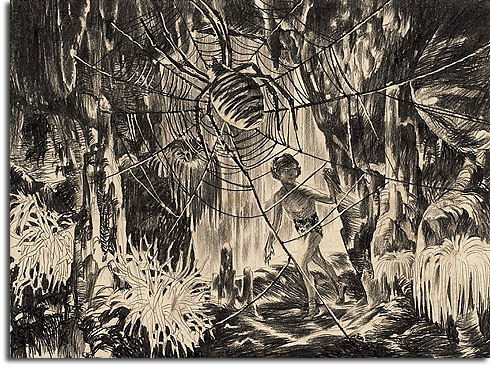

This really fantastic sketch was drawn for the production of Tarzan Finds a Son! starring Johnny Weismuller, 1939

This really fantastic sketch was drawn for the production of Tarzan Finds a Son! starring Johnny Weismuller, 1939Herb needed a break from the design department when he decided to take a trip to the Orient, inspired by his work on MGM’s The Good Earth. After circumnavigating the globe and witnessing a world in flux, he returned to Hollywood. He missed a chance to serve as art director for Gone with the Wind, but while teaching art classes at the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles one of his exhibitions of watercolors caught the eye of some artists from the Walt Disney Studios… But those are all stories for next time.

Coming up: Herb travels the world, works for the mouse, and then leaves… Only to come back. Disneyland, Siam, EPCOT and Emmett Kelly await…

Images for theses stories come from a variety of sources, notably A Brush with Disney (2000), but special thanks must go to John Donaldson, author of Warp and Weft: Life Canvas of Herbert Ryman.

His MGM stuff is truly outstanding. I wonder how much time he took to do those sketches. Almost everyone in the hall is in motion, thinking or doing something. Herb was great with a crowd.

I love his crowds in his later Disney renderings. Crowds in art that comes out today seems so forced to me – like they’re screaming LOOK HOW MUCH FUN WE’RE HAVING!

Herb’s were all natural. They were an obvious presence, but didn’t overwhelm the actual point of the artwork.

I really love the one from Tarzan. So moody…